- LIVINGSTONE

CREEK, YUKON:

A COMPENDIUM HISTORY ↑ - Acknowledgements ↑

- Forward ↑

- Livingstone Creek Chronology ↑

- Rocks,

Gravel & Gold:

Geology Notes of Livingstone Creek Area ↑ - First Nations Presence in the Livingstone Creek Area ↑

- A

Summary History Of Livingstone Creek, YT, 1897-1930 ↑

- A Summary

History of Livingstone Creek, Y.T. ↑

- Prelude ↑

- Discovery ↑

- Mining Activities 1892-1902 ↑

- Transportation ↑

- Mining Activities 1903-1915 ↑

- Comparison of Livingstone with other mining communities ↑

- North-West Mounted Police post and population numbers ↑

- Livingstone Town ↑

- Mining Activities 1911-1925 ↑

- Demise of Livingstone Creek 1930s ↑

- Closing notes ↑

- Endnotes ↑

- A Summary

History of Livingstone Creek, Y.T. ↑

- Aviation History of Livingstone Creek ↑

- Livingstone Creek

Biographies ↑

- Biographies Forward ↑

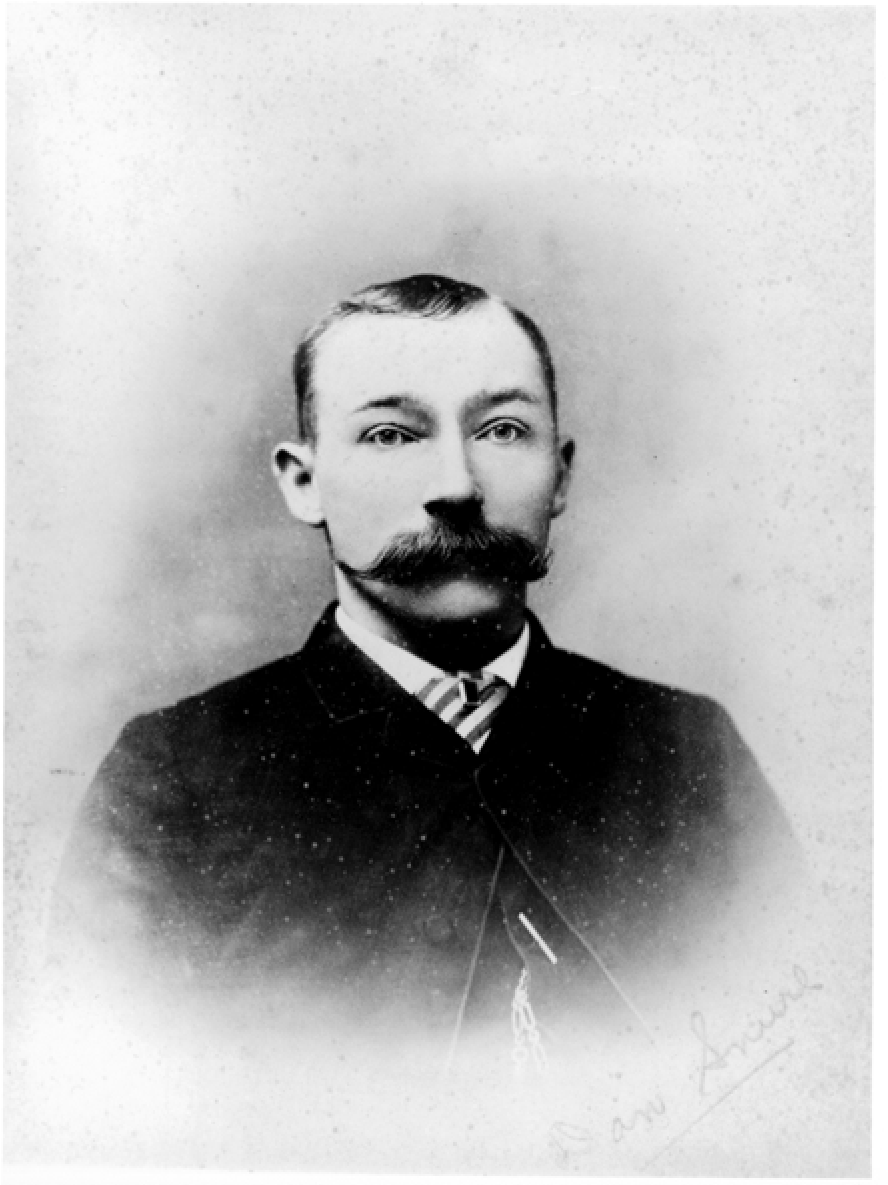

- J. E. Peters ↑

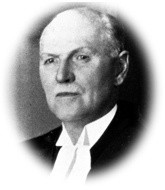

- George Black ↑

- Daniel G. Snure ↑

- The Clethero (Cletheroe) Family ↑

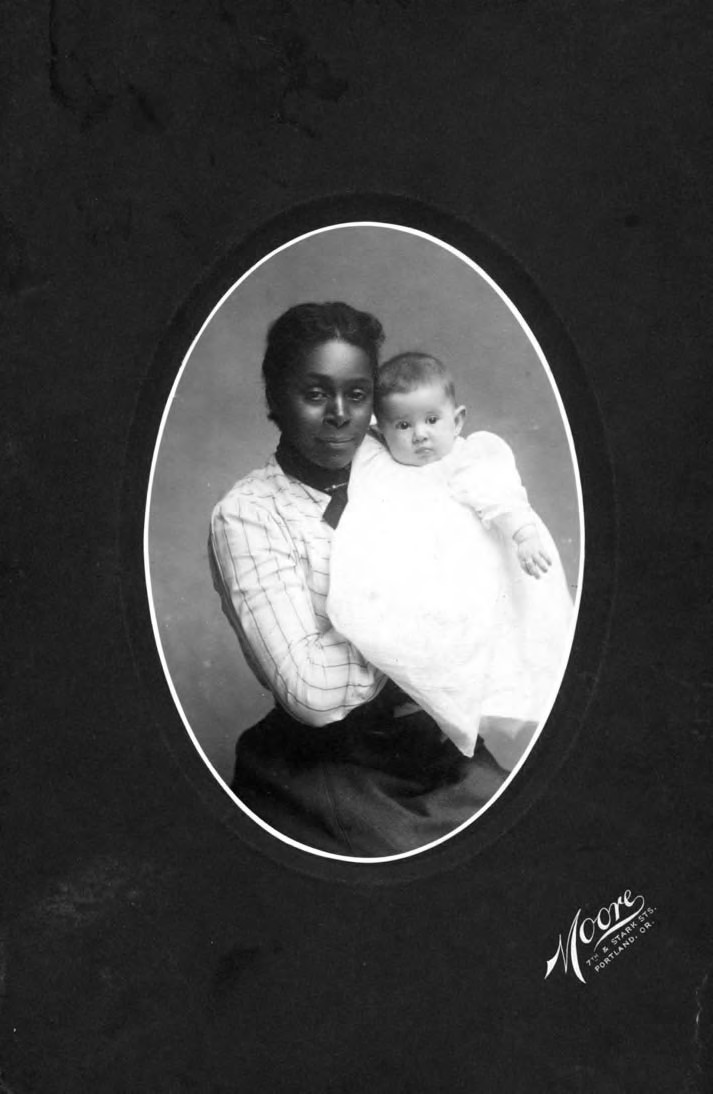

- Lillian Mabel Taylor ↑

- “Stampede” John Stenbraten ↑

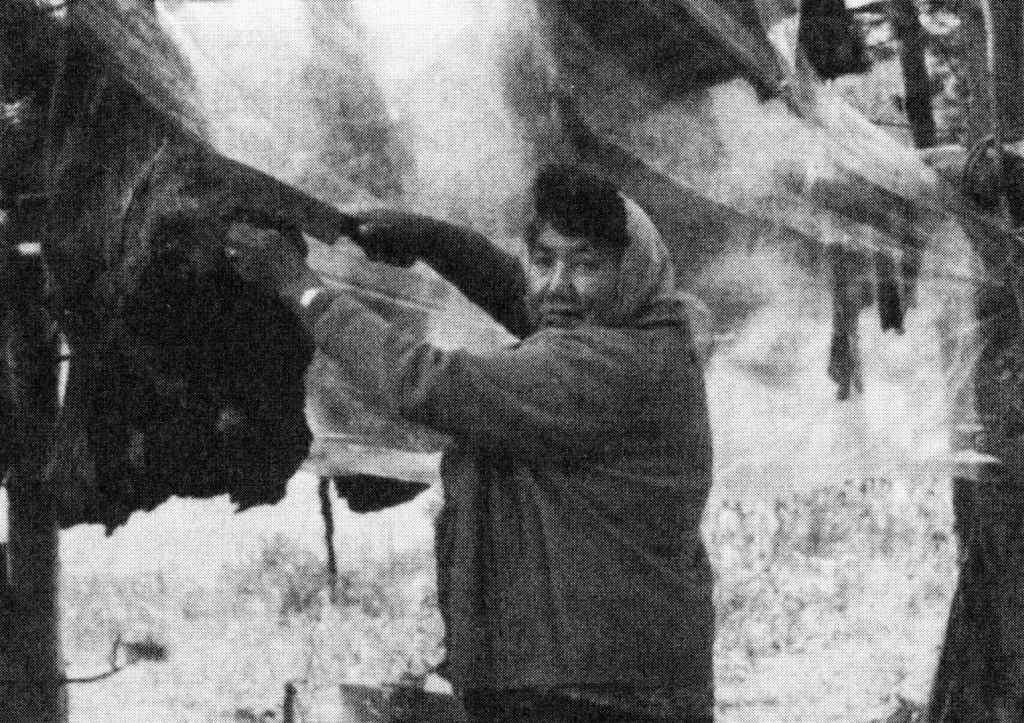

- Frank Slim ↑

- Clem Emminger ↑

- Thomas and Beda Louise Kerruish ↑

- Louis Engle ↑

- Nakamura Family ↑

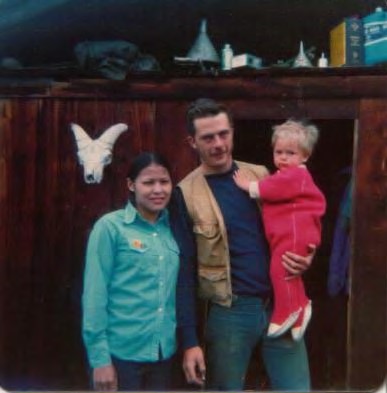

- Al & Maria (nee Bjorkes) Serafinchon ↑

- Fuerstner Family ↑

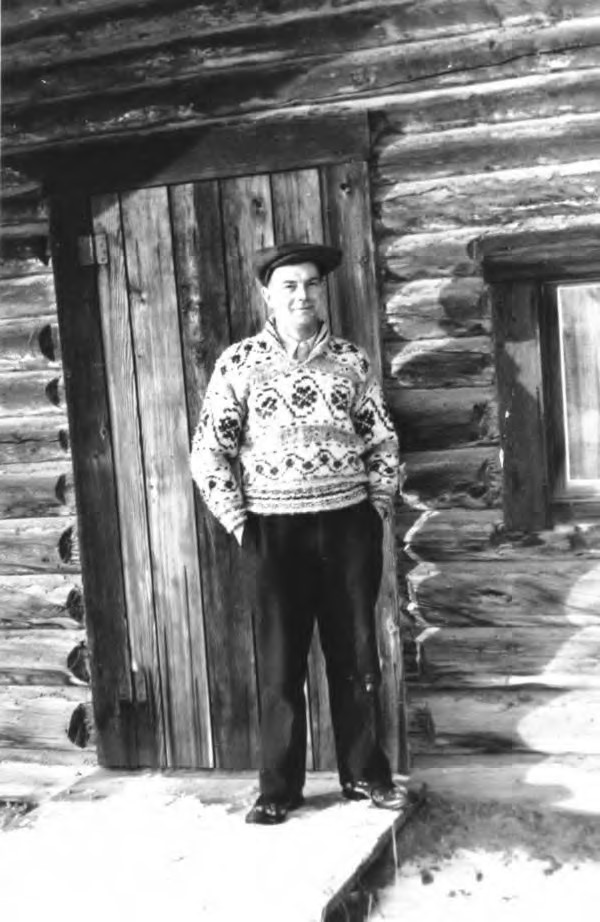

- Gerry (Gerald) David McCully ↑

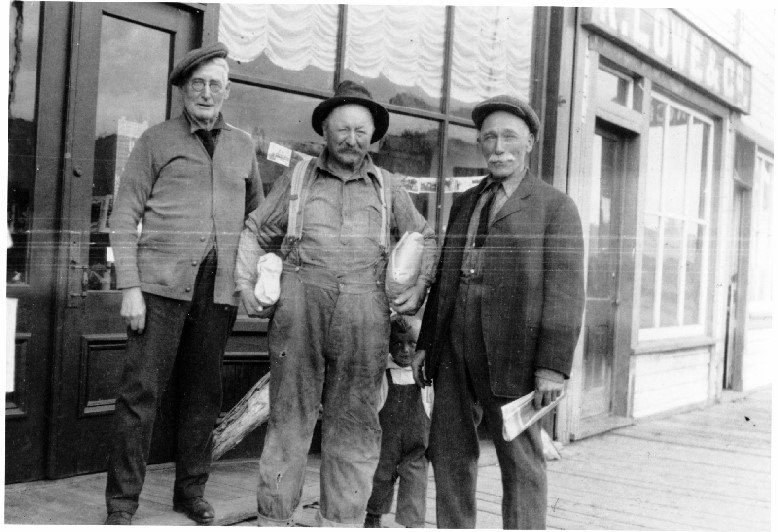

- Additional Notes & Photos of Livingstone Creek Area Residents ↑

- Slim Foster ↑

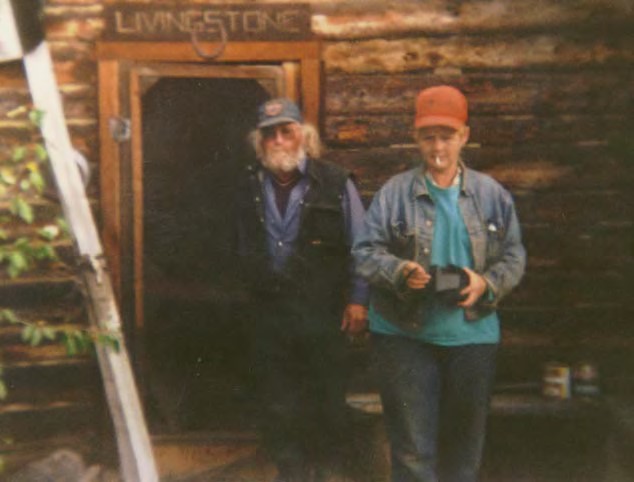

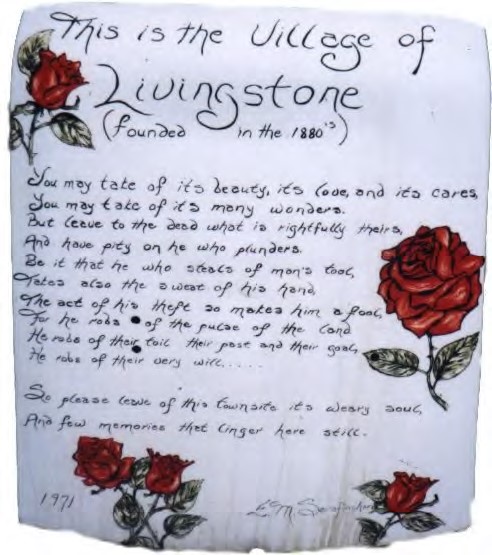

- Livingstone Creek Village ↑

- Livingstone Creek Preservation Issues ↑

- Sources Consulted ↑

- Books, Newspapers, Publications, & Reports ↑

- Film & Video ↑

- Interviews ↑

- Maps ↑

- Photographs ↑

- Diary Transcripts, Yukon Archives Manuscripts ↑

- Website ↑

- Additional Sources ↑

- Livingstone Creek Heritage Inventory: Document Listing From Heritage Branch file # 4057-10-49 ↑

- Livingstone Creek Heritage Inventory: Document Listing From Heritage Branch file # 4057-10-49 cont’d ↑

- Documents pertaining to transfer of Federal Reserve 105E08-001 ↑

LIVINGSTONE

CREEK, YUKON:

A COMPENDIUM HISTORY ↑

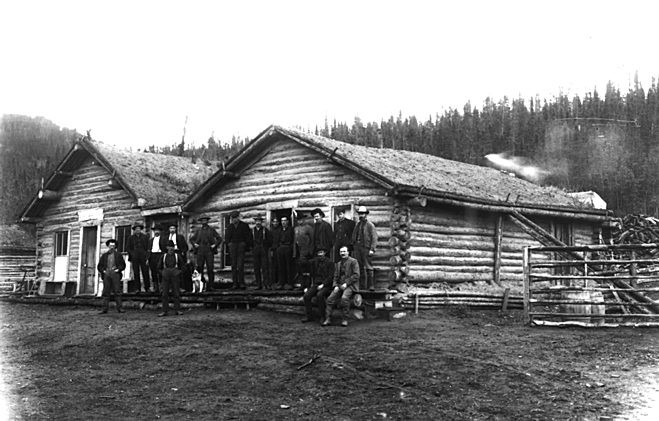

Livingstone Creek ca. 1906, YA 2002-1-118 #349, E.J. Hamacher fonds

Prepared for Heritage Resources, Yukon Government

By: Leslie Hamson

Whitehorse, Yukon

May 2006

Copyright Heritage Resources Unit, Yukon Government 2006

The information and photos in this report are the property of the contributors. Their permission must be obtained for use in publications in any media including film.

For contributors’ contact information, contact:

Heritage Resources Unit

Government of Yukon

Box 2703,

Whitehorse, YT Y1A 2C6 867-667-5386 heritage.resources@gov.yk.ca

Versions

1.0 Livingstone Creek Report Master (May 2006)

1.1 Livingstone Creek Report Master + Bennett report (Nov 2019)

1.1.1 Livingstone Creek Report Master + Bennett report – for web (Feb 2023) Formatting anomalies may remain; cross reference numbers for foot- and endnotes have not been verified.

Acknowledgements ↑

The Livingstone Creek Heritage Inventory and the Livingstone Creek, Yukon: A Compendium History report was researched and compiled by North Words Consulting under contract to the Heritage Resources Unit, Government of Yukon, 2001 – 2003. The Unit also provided considerable technical, material, and personal support through 20042005.

Additional support came from the Yukon Foundation through the Doris &John Stenbraten Fund and Roy Minter funds, and through an invitation to present the first phase of the project at the Foundation’s 2003 AGM.

Yukon Archives offered access to materials, advice, and consultation, and acknowledged the project in the annual Donor Appreciation night, 2003.

MacBride Museum gave access to files. The Energy, Mines & Resources Library allowed viewing of a video. The department also provided a map. Many thanks are offered by the contractor to all of the above for these substantial commitments.

Special gratitude goes to the private individuals who granted interviews and access to their photographs, videos and documents. Several of these people have now donated their materials to Yukon Archives, adding important new documentation on Livingstone Creek and area.

Contributors to data in the finding aid include Frances Clethero Woolsey, Donna Wilson,

Eva & Emil Stehelin, Jim Robb, Pearl Keenan, May Suits Getz, Margaret & Rolf Hougen, Bill Webber, Ken Jones, Gerald (Gerry) David McCully, Goodie Sparling, and Bob Cameron.

Thanks go also to contributors to the report phase of the project: Gordon Bennett, whose

1970s study for Parks Canada comprises a substantial section; Charlie Roots for his Rocks, Gravel and Gold geology report, and Al and Maria Serafinchon for their personal account, Time Spent at Livingstone Creek, and for their many hours providing additional documentation and assistance. Frances Clethero Woolsey, Alice Cletheroe McGuire, Goodie Sparling, Lloyd Ryder, Max Fuerstner Jr., Joyce Hayden, Helene Dobrowolsky, Melanie Needham, Mike Mancini, Sharon Pullen, and Carmelle Besler all provided information and support of various kinds.

The contractor offers special thanks to the forbearing and patient staff at the Heritage Resource Unit, and to Sophie Partridge of Yukon Foundation.

Forward ↑

The Livingstone Creek research project consisted of two main phases: heritage inventory and the research report (the present document).

Heritage Inventory ↑

The Livingstone Creek Heritage Inventory (LCHI) was researched and compiled by

North Words Consulting under contract to the Heritage Resources Unit, Government of

Yukon, 2001 – 2003, with additional support from the Yukon Foundation: Doris and John Stenbraten Fund & Roy Minter funds. Livingstone Creek, Yukon: A Compendium History is the outgrowth of an initial project to inventory available documentation on the Livingstone Creek area.

The inventory project examined documents, journals, maps, images, and videos held at

Yukon Archives, Heritage Resources Unit, MacBride Museum, Energy Mines and Resources Library, Parks Canada, and several private collections, some of which were donated to Yukon Archives through the activities of the project. A limited number of interviews were conducted; of those that were taped, the recordings and transcripts were donated to Yukon Archives.

The inventory product (Livingstone Creek Heritage Inventory) consists of a finding aid in the form of image and document databases. The databases were printed out and assembled into binders. Copies were deposited with Yukon Archives, Heritage Resources Unit, Yukon Foundation and North Words Consulting. Intended as a guide for researchers, students, and those with a general interest in Yukon and mining history, the finding aid is designed to be added to and corrected as more information becomes available. Users of these aids are encouraged to add their notes and to contact the addresses below.

Research report ↑

Livingstone Creek, Yukon: A Compendium History is a loosely constructed collection of articles covering a range of topics by various authors. The tone ranges from formal and scholarly to gossipy and colloquial. In two instances, excerpts from personal diaries are used. Some articles by the editor are based on interviews. The report includes biographical sketches of just a few of the many people who lived and worked in the area. Some information is repeated section to section as it is presumed that some readers may want to read only specific articles. Most photographs are from the personal collections of contributors. Others are from Yukon Archives and the Heritage Resources Unit.

Personal names and place names are given a variety of spellings in the source documents and interviews. Livingstone is sometimes noted as “Livingston”, and Mendocino is also known as “Mendocina.” The community of Livingstone Creek is known variously as a town, village, or camp. When personal names have varying spellings, the one most frequently noted is used; in the instance where a living informant knew the individual, their memory is relied upon.

Selection of material was a difficult task, and much more has been omitted than is represented. Some important information about contemporary individuals and recent activity was not available until too late in the project to be included. With reluctance, some information that could not be verified has been included, with the expectation that readers will respond with corrections and verifications.

Readers are invited to submit notice of errors, omissions, or leads to additional sources, to the addresses that follow.

Heritage Resources Unit Government of Yukon Box 2703, Whitehorse Yukon, Y1A 2C6 867-667-5386 |

North Words Consulting 83-12 Ave Whitehorse, Yukon, Y1A 4K2 Ph. (867) 633-4358 Fax (867) 633-4094 |

|---|

northword@polarcom.com

-Leslie Hamson, May, 2006

Acronyms used in report ↑

| CBC | Canadian Broadcasting Corporation | |

|---|---|---|

| DIAND | Department of Indian Affairs & Northern Development | |

| HB | Heritage Branch | |

| HRU | Heritage Resources Unit (formerly Heritage Branch) | |

| HSMB | Historic Sites Management Board (Canada) | |

| LCHI | Livingstone Creek Heritage Inventory | |

| YA | Yukon Archives | |

| YHS | Yukon Historic Sites (part of Heritage Resources Unit) |

Livingstone Creek Chronology ↑

Livingstone Creek Chronology ↑

Sources are those quoted in the report. See footnotes and endnotes in report sections.

| DATE | PERSONS, ENTITY OR ISSUE | EVENT |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-1881 | Ta’an Kwäch'än & Tagish Kwan | Traditional use of lands and resources in area. Livingstone is within the traditional territory. |

| 1881 | Big Salmon River (“Iyon”) | Four men prospect along 200 miles, panning and finding colours. |

| 1894 | J.E. (James Edwin) Peters | Prospects Livingstone Creek. |

| 1898 or 1899 | Jospeh Peters. Peters, George Black, Sam Lough |

Stake Discovery Claim, Livingstone Creek; $3,600 gold reported by Black & Lough. |

| 1900 | NWMP Census | Census shows 84 people on Livingstone Creek. Fluctuates 60 – 125 to year 1910. 1907 estimate of summer pop. of 100, winter 35 – 50 exclusive of children. |

| J. E. (James Edwin) Peters | Claim on Lower Discovery yields $10,000. | |

| Livingstone Creek Syndicate | Buys claims 1-6 below Discovery at public auction. | |

| Daniel G. Snure | Moves from roadhouse on Hootalinqua to roadhouse at Livingstone. | |

| Transportation | British Yukon Navigation Co SS Bailey makes occasional trips to Mason’s Landing but refuses to give regular service. The SS Quick owned by Thomas Smith fills the gap. | |

| 1901 | NWMP | Post of three buildings established on wagon road, 150 yards south of creek, due to “great influx of people into the Big Salmon district.” Duties included affidavits, issuing free miners’ certificates, acting as sub-mining recorder, crown timber & land agent. |

| Summit Creek | Named by prospector Meany. | |

| Transportation | Miners blaze 15-mile pack trail between Mason’s Landing on the E. side Teslin River & South Fork of Big Salmon and rough in winter trail to Upper Laberge 1901-1902. |

|

| Bob McIntosh | Closes his ‘hotel’ for the winter with plans to return in the spring. Unknown whether he does. | |

| 1902 | Transportation | Gov’t constructs 16-mile, $1700 wagon road Mason’s Landing to No. 10 below Discovery. |

William Clethero/Cletheroe |

Mining on Little Violet Creek along with “Dutch” Henry Broeren. Cletheroe & family remain in district intermittently to 1953, when William Cletheroe dies. Other Ta’an Kwäch'än families also participate in mining over the years. |

| DATE | PERSONS, ENTITY OR ISSUE | EVENT |

|---|---|---|

| 1902 (cont’d) | NWMP- roadhouses | Cpl. Ackland notes two licensed & two unlicensed roadhouses, & general store. |

| Lillian Mabel Taylor | Cook and launderer at Livingstone arrives, stays to 1909. | |

| 1903 | Transportation | Miners’ “makeshift” trail improved to “fair onehorse” by NWMP & miners. |

| Mining Recorder Office | Moved from Hootalinqua to Livingstone Creek. L. Pacaud MR 1903-1905. | |

| Livingstone Creek Syndicate | 15 men employed. Creek produced $100,000; profit of $20,000. | |

| May Creek | Named for Samuel May who prospected for many years after 1903. | |

| 1904 | Decline of $40,000 output; late spring, early frost. | |

| RNWMP | “Royal” added to NWMP name. | |

| 1905 | May Creek nugget | 39 ounce nugget found, largest to date for area. |

| Livingstone Creek Syndicate | New pay streak discovered in old creek channel. $100,000 produced. Output fluctuates $35,000 - $100,000 yearly until protracted decline beginning 1910. | |

| 1906 | “Stampede” John Stenbraten | Active in district into 1940s. |

| 1907 | Telegraph | Telegraph line put in. Dan G. Snure operator. |

| 1908 | Livingstone Creek Syndicate & other | Limited mining in district. |

| Post Office | Established after miners carry cost of delivery since 1905. Dan Snure postmaster. PO closed 1915. | |

| 1909 | Heavy rainfall; miners predict claims will be worked out by 1910. | |

| Lillian Mabel Taylor | Leaves Livingstone likely for Whitehorse | |

| 1910 | NWMP | Detachment withdrawn over winter of 19101911; patrols made until 1912. |

| Gold estimate for decade | Bennett’s report written ca. 1978 quotes estimated $1 million overall, most of which came out 1900 – 1910, and does not include activity after 1910. For more current total, consult Mining Recorder office in Whitehorse. | |

| Dan (Daniel) G. Snure | Acts as agent to mining recorder until 1925, also runs road house, retails general merchandise, is postmaster, owns mining claims. | |

| 1911 | Population | Levels off to 30. |

| International Mining Co | Working No. 21-26 below Discovery, without much success. | |

| 1912 | Mining | “…unusually quiet”- Department of Interior annual report. |

| DATE | PERSONS, ENTITY OR ISSUE | EVENT |

|---|---|---|

| 1914 | James Geary hydraulics for A.C. Company; A. Officer drives in thawed ground for good pay; George Bruce works open pit on Summit; L. Keyzer runs hydraulic plant on Cottoneva, finds $215 nugget; W. Cameron works head of Sheehan’s Gulch, No 1 above Discovery; Harry Barry drives adit 350 feet. | |

| 1915 | Post Office | Closed. |

| Mining | New pay streak on old claim discovered, but poor yields in 1916. | |

| 1916 | Mining | 26 miners produce 546.39 ounces- $8,195.85 |

| 1917 | 485.97 ounce- $7,289.55 @ $15 ounce. | |

| 1920 | Mining | Limited mining, mostly prospecting. No more than six or seven men operating in district throughout 1920s. |

| 1925 | Dan Snure | Resigns as agent to mining recorder; no evidence of anyone in that role thereafter. |

| 1930s-1960s | Various people | Frank Slim, Clem Emminger, Louis Engle, Tom & Beda Kerruish, Geary brothers, and others continue some level of trapping, prospecting and mining. Bill Geary & wife run stagecoach. |

| 1938 | Air strip | Runway created by pulling stumps by hand or with horses in meadow one mile from South Fork of Big Salmon River, three miles west of Livingstone townsite. First recorded flight in May by Trimotor Ford piloted by Ev Wasson & Buck Stone, passengers Livingstone miners. Cable car used to get to Livingstone side of river. |

| 1950s | Air strip | 2nd airstrip 100 x 1200’ built by Louis Engle with D2 Cat. |

| 1967 | Mining Preservation issues |

Max Fuerstner & Erwin Kreft stake claim on Livingstone. At this time the village is in remarkably good condition; cabins are furnished and many mining and household artefacts are in situ. |

| 1971-1973 | Upper Lake Creek | Ed Hill, Augie Trexler, Dick & Lela Young, Todd & Fern Ames from Washington State mine. Hill’s property sold to Ed Kosmenko in 1976. |

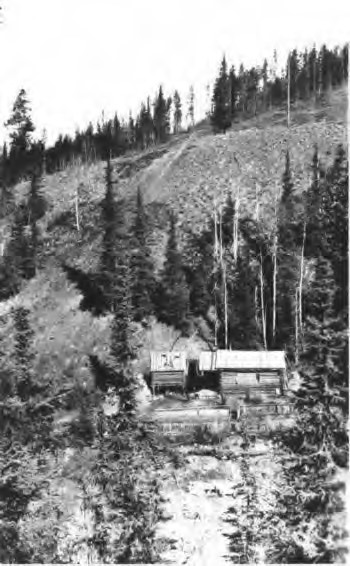

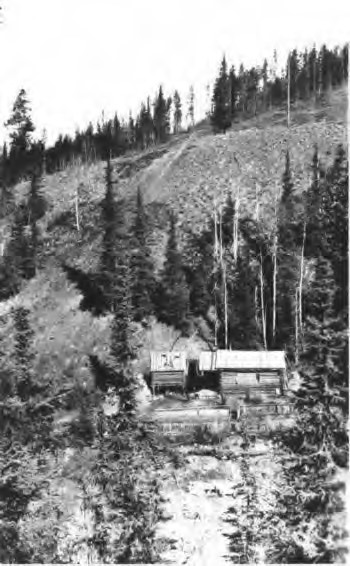

| 1971 | Constellation Mines | Ace Parker, Gerry McCully, Maria Bjorkes Serafinchon and Al Serafinchon form an association to placer mine Livingstone Creek, Cottoneva Creek and Lake Creek, with percentage interests to Louis Engle & George Asuchak for ground. |

| DATE | PERSONS, ENTITY OR ISSUE | EVENT |

|---|---|---|

| 1971 (cont’d) | Winter road | New road built with some assistance from government tote road program. |

| Air Strip | Engle’s airstrip is enlarged to 250’ x 1800’. | |

| 1972 | Mining | Constellation Mines begins operations on Louis Engle’s old claims. Serafinchons leave association; remain active in the area as miners & trappers until 1986. Nakaumuras mine Mendocina into the 1980s; Asuchaks mine Lake Creek. |

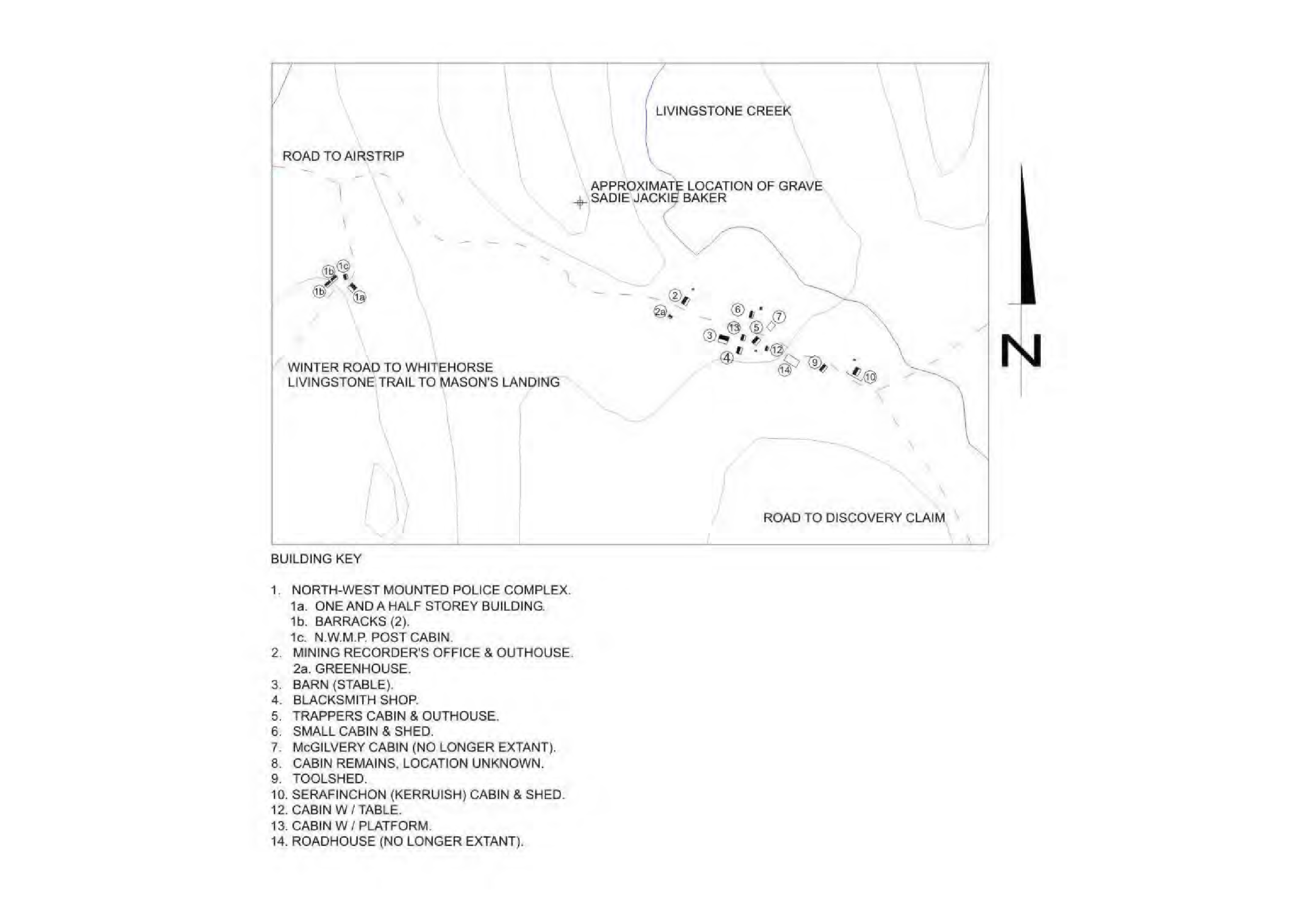

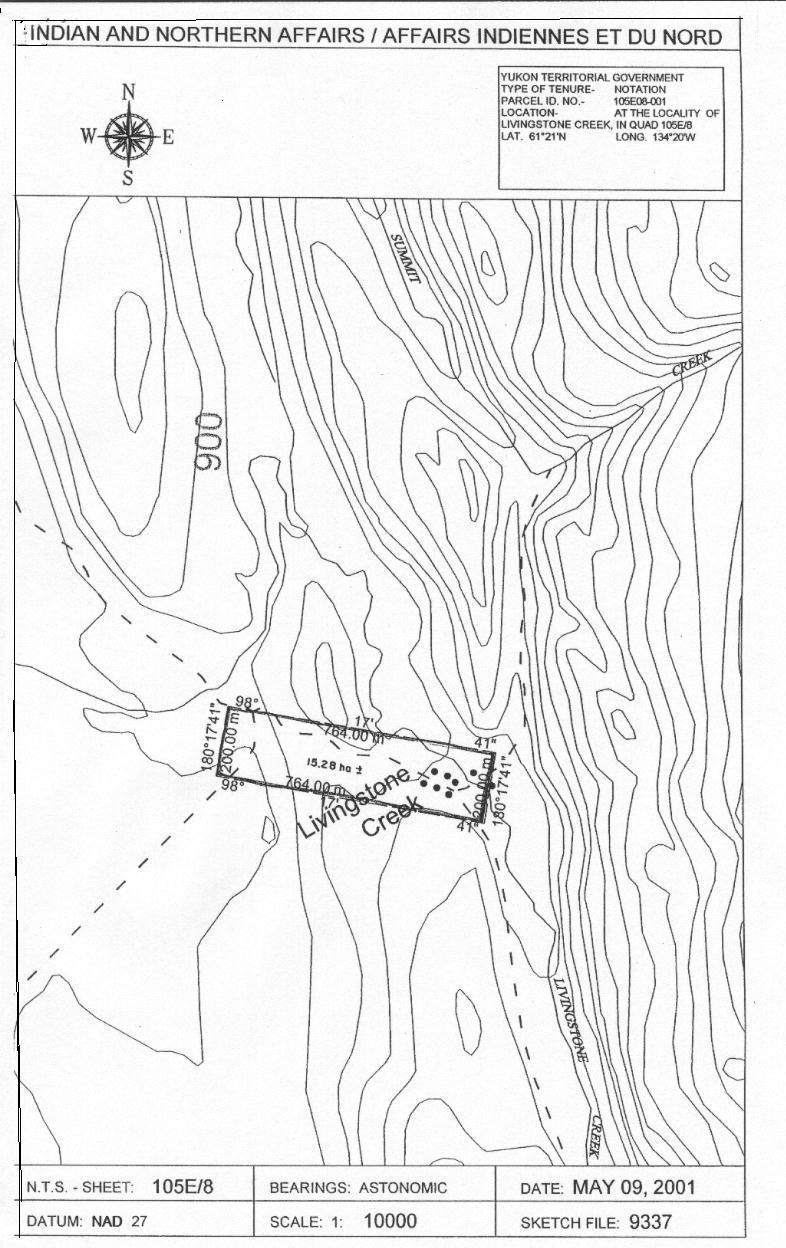

| 1973 | Historic reserve status | The Livingstone Creek village and NWMP are made a DIAND (Department of Indian and Northern Development) reserve for review by HSMB (Historic Sites Monument Board Canada), #9337, 81.2 hectares in size, Quad 105E/8. No preservation work undertaken. Eventually (date unknown, but by 1980) HSMB decides against designation as National Historic Site. |

| Preservation issues | Many artefacts have been taken from the village, apparently removed by helicopter. Current residents provide protection from theft during mining season but more artefacts are taken over the winter. | |

| 1974 | Mining | New partners Max Fuerstner Sr. & Bob Miller bring resources to cash-strapped Constellation Mines. Gold prices rise. Mining activity on other creeks by other parties, including Moose Creek. |

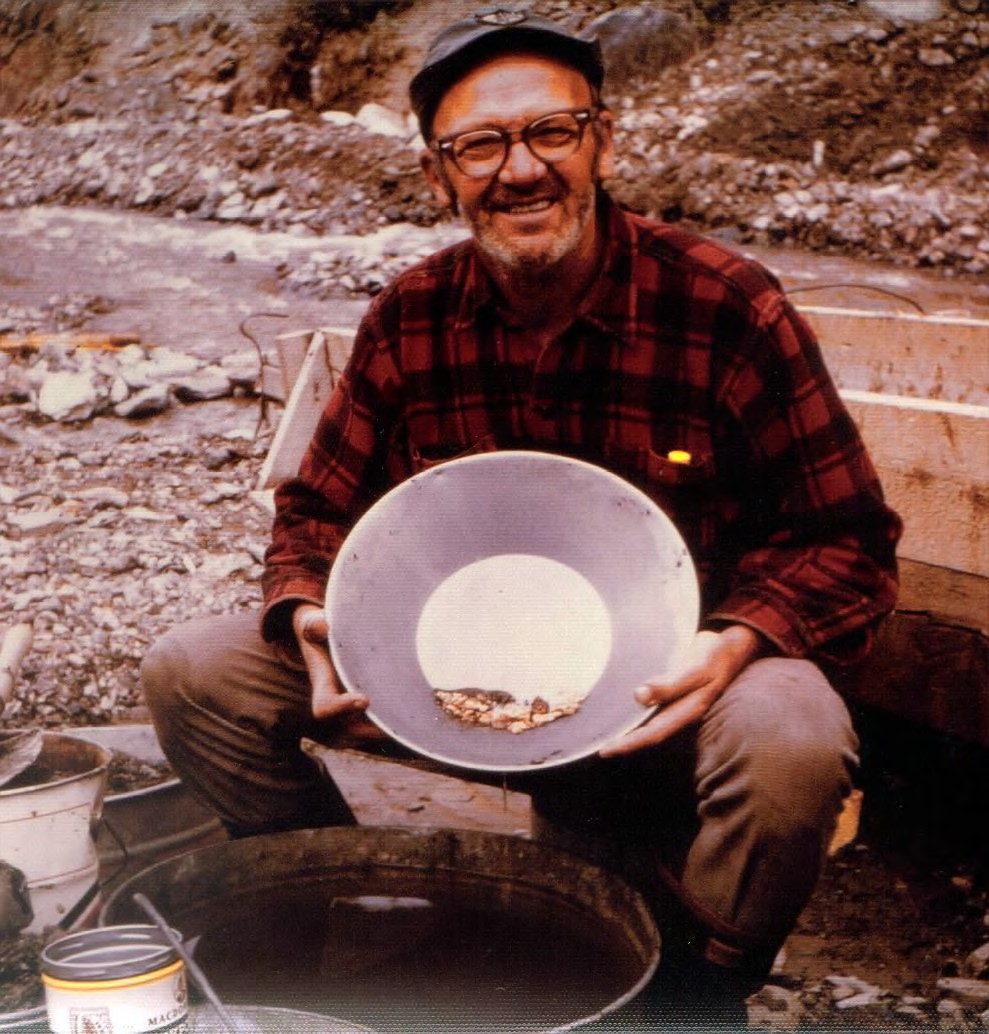

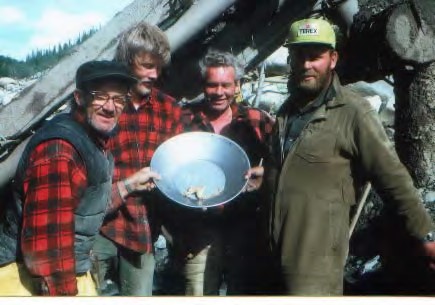

| Large nugget finds | July 21 1974 20 ½ ounce nugget found by Constellation Mines on Livingstone Creek, valued at $6,000 - $10,000, sold in 2004 for $30,000. An earlier find was made by Louis Engle (date uncertain) of a 21 ½ ounce nugget upstream. A 39 ounce nugget was found on Summit Creek (date not known). See also 1997 below. | |

| 1977 | Mining | Name Constellation Mines dropped. Partnership consists solely of Max Fuerstner Sr. and Bob Miller. Miller buys out in 1981. |

| 1978 | Mining | Serafinchons and Frank & Phyllis Brown join Max Fuerstner Sr. as partners on Livingstone Creek. Canada Tungsten provides investment to upgrade equipment. |

| DATE | PERSONS, ENTITY OR ISSUE | EVENT |

|---|---|---|

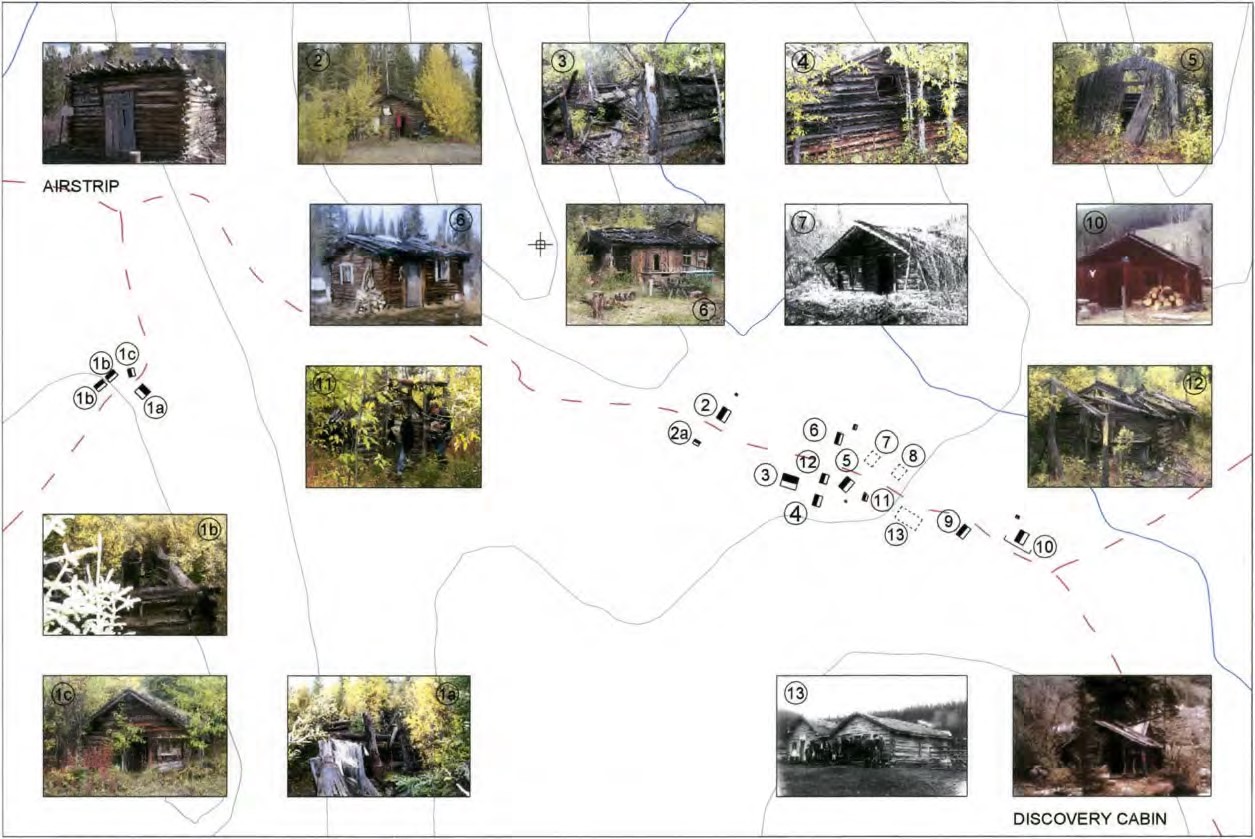

| 1980 | Historic reserve status | Parks & Historic Resources Branch, Dept of Renewable Resources (later called Yukon Historic Sites, Heritage Resources Unit) conducts building survey of the five structures at the NWMP post and 10 at the townsite, photographing and reporting on conditions. Some level of preservation assistance is requested by residents, and recommended in report, but is not acted upon. |

| 1983 | Mining | Max Fuerstner Jr. assumes full mining decision authority in 1983. As Livingstone Placers Ltd. he mines Livingstone, Summit, Cottoneva & Mendocina Creeks. |

| 1984 | Preservation issues | Fuerstner & company moves out of village into trailer camp. Village buildings deteriorate rapidly with “no-one to keep the heat on”— Max Fuerstner Jr. |

| 1992-1995 | Preservation issues | Donna Wilson & Gordie Lautamus mine in the district. Extensive correspondence from Wilson to Heritage Branch expressing preservation concerns for the Livingstone village. |

| 1997 | Big nugget find | 36.6 ounce nugget found by Max Fuerstner Jr. |

1993, 1996, 2000 |

Preservation issues | DIAND & Yukon Historic Sites (Heritage Branch) make inspection trips and photograph and videotape structures. No preservation measures taken. By 2000 all buildings but one are seriously deteriorated. |

| 2000 | Mining | Max Fuerstner Jr. moves operation to Mayo district, but retains 200 claims on Livingstone through to Mendocina creeks. Minimal activity on other creeks by other miners. |

| 2001 | Historic reserve | Yukon Land Records registers change of size from 81.2 to 15.28 hectares. |

| 2003 | Mining | Little Violet Creek the only active mine site. Doug Gonder retains interests on Martin Creek, and Gordie Ryder on Sylvia Creek. |

| 2005 | Mining | Fuerstner plans to move drilling rig in over the winter and begin hard rock drilling in the summer. |

Rocks,

Gravel & Gold:

Geology Notes of Livingstone Creek Area ↑

By Charlie Roots, Yukon Geological Survey

Sheehan’s Gulch, Livingstone Creek, YA 2002-48 Photo #46, Donna Wilson fonds

Flying towards Livingstone Creek, one sees spur ridges of the Big Salmon Range, with slopes of spruce and dwarf birch sweeping up to rocky ribs. Fast, rushing streams drain the range westward to the broad valley of the South Big Salmon River. The shallow, rocky bottom and gravel bars along the curving banks are flooded in late June, but nearly dry by late summer.

Initially the valley provided good hunting and was used as a direct route between the Teslin and Big Salmon rivers. When gold was discovered the settlement of Livingstone was established near the mouth of the most important creek.

1. Bedrock ↑

The Big Salmon Range contains metamorphosed rocks that were deposited on a seafloor between 300 and 500 million years ago, in the early Paleozoic era. The black mud on the bottom was interlayered with fine sand settling through the sea far from river mouths. Layers of tough green rock are the remains from submarine lava flows.

This part of central Yukon was crumpled by the collision of ancient North America as it inexorably moved westward, collapsing volcanic islands and uplifting the old seafloor. The mountains were formed between 180 and 100 million years ago (Jurassic to Early Cretaceous periods). The sediments were compressed, forming quartzite and schist – the rocks now seen in the canyons of the creeks.

2. Source of the gold ↑

Eleven tributary creeks of the South Big Salmon River contain placer gold: Dycer,

Mendocino, Little Violet, Cottoneva, Lake Creek, Summit, Livingstone, Martin, Sylvia, Moose and Fish. The gold is found where the streams flow into the valley. No gold, however, has been found in the bedrock of the Big Salmon Range; it appears to come from the small quartz veins that occur in the creek canyons immediately upstream.

The streams cross broad bands of these rock types. The rocks are faulted. The abundant graphite and mica in the rocks acted like grease when they were deformed.

During uplift of the rocks, cracks formed and warm water pulsed through the fractures. Quartz and small quantities of gold were precipitated –like the white salt crust that forms in the kettle or a hot water tank. Eroded by the streams, these crack fillings released their gold, which was winnowed from the less dense rock by the turbulent stream. Scientists have extracted gold from the quartz-filled fractures in the canyon and found the same trace element proportions as that of nuggets mined from the gravel downstream (Stroink and Friedrich, 1992).

3. Burial and preservation of the Livingstone gold-bearing gravel ↑

Like all of eastern Yukon, the Livingstone area was completely covered by thick ice sheets many times during the last two million years. As the climate warmed after each glacial maximum, ice melted from the mountaintops and large glacier tongues moved northwest down the South Big Salmon River valley. The side valleys escaped scouring by the glacier, leaving the gold-rich, pre-Ice Age gravel undisturbed.

As the ice receded, a blanket of mud and stones previously carried by the glacier lay on the valley floor. Rushing rivers of glacial meltwater redistributed the layers of glacial mud and stones (Levson, 1992). Dammed by a wall of ice downstream, the water backed up in the valley, depositing silt and sand terraces high on the valley walls. The modern streams have only had the last 12,000 years to erode through the accumulated layers of lake silt, river gravel and glacial till, to once again expose the pre-Ice-Age gravel where the pay-streak lies. The challenge for the early miners was to follow the buried original stream channel, because the modern stream in places chose a different course.

Summary ↑

The rich deposits of coarse gold on the east side of the South Big Salmon River differ from most Yukon placer deposits because they lie well within the area covered by continental glaciation. The layering of overlying sands and gravel records a series of glacial, river and lake environments before its current exposure by streams and mining. The source of the gold is small quartz veins in the dark schistose rock of the area. It was eroded from the rock before the Ice Age, locally remobilized by streams between glaciations, and escaped scour by valley-filling ice.

References ↑

Bostock, H.S. and Lees, E.J., 1938 (reprinted 1960). Laberge map area, Yukon. Geological Survey of Canada, Memoir 217. 32 p. (Includes most references to earlier reports of the gold camp).

Levson, V., 1992. The sedimentology of Pleistocene deposits associated with placer gold-bearing gravels in Livingstone Creek area, Yukon Territory. In: Yukon Geology, Vol. 3; Exploration and Geological Services Division, Yukon, Indian and Northern Affairs, Canada, p. 99-132.

Stroink, L. and Friedrich, G., 1992. Gold-Sulphide quartz veins in metamorphic rock as a possible source for placer gold in the Livingstone Creek area, Yukon Territory, Canada. In: Yukon Geology, Vol. 3; Exploration and Geological Services Division, Yukon, Indian and Northern Affairs, Canada, p. 87-98.

First Nations Presence in the Livingstone Creek Area ↑

Lake LaBerge, S.E. view from Deep Creek, looking towards Livingstone Trail. Photo: Yukon Government

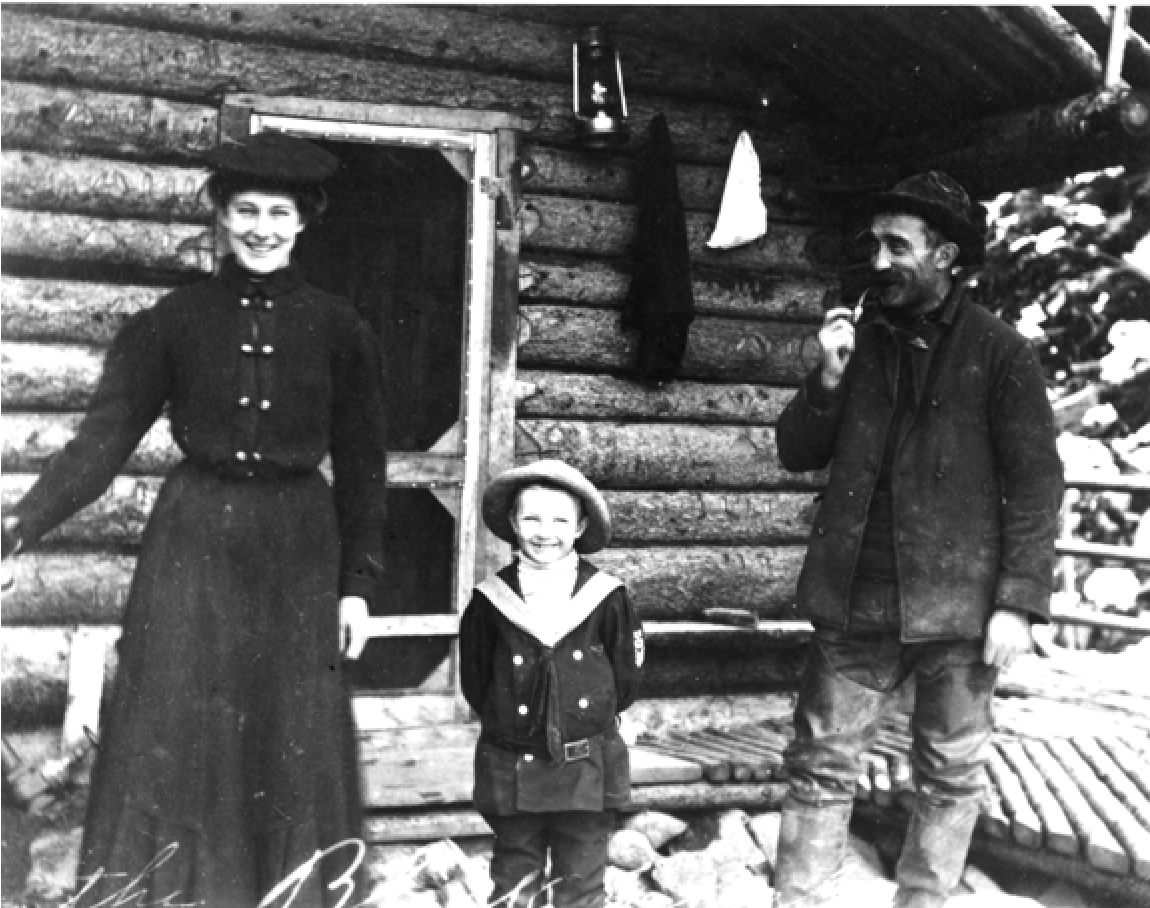

Long before mining activity began in the Livingstone Creek district, the area was used by Tàa’an Kwäch’än,1 Tagish Kwan and Teslin people for hunting, fishing, and gathering. Later, the families participated as miners, freighters, trappers, and as suppliers of game meat for the Livingstone village.

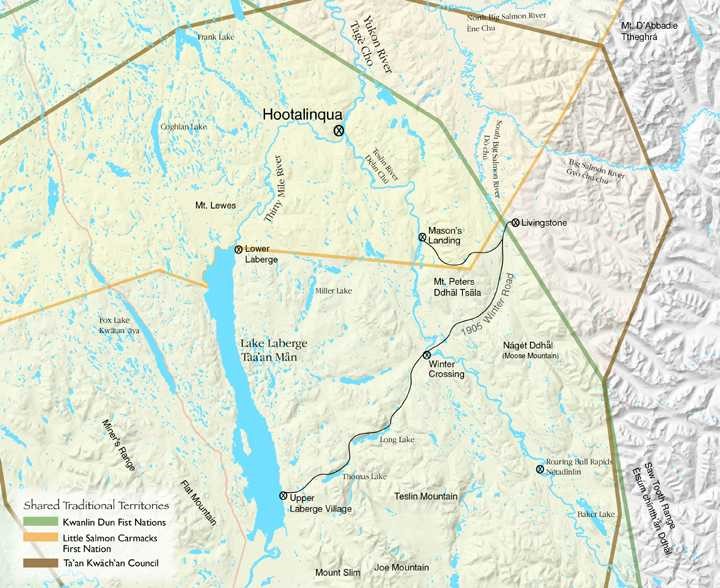

The ancestral lands of the Ta'an Kwäch’än (“people of the flat lake place”) extends from Hootalinqua to the McClintock Valley and west from the White Bank village (31 Mile) at the confluence of the Takhini and Little Rivers and east to Winter Crossing on the Teslin River. Their northeast territory extends to Livingstone Creek and the area below the confluence of the Big Salmon and the South Big Salmon River.2

One group of Ta'an Kwäch’än families trace their ancestry back to Lande, from Tagish, and Mundessa (Old Man Chief) from Hutshi. Mundessa and Lande had several children:

Shuwateen (Maggie Boss), Kashxoot (Chief Jim Boss), Tusaxal (Jenny Boss), Shaan Tlein (Susie Boss), and a second son Undeahel.3

Maggie Boss and her first husband, Dawson Jim, had two children, Kitty and Elsie.

Maggie Boss and her second husband, "Dutch" Henry Broeren, had seven children:

Celia, Alice, Aggie, Charlie, George, John and Willie.2 References to this family are found in the 1904-1905 journal attributed to Lillian Mabel Taylor3 and in the storytelling session about Livingstone Creek and area by Clem Emminger recorded by John Scott in 1965.4 Emminger also makes a number of references to Jim Boss.

Jenny Boss married Dawson Jim and had children George, Ida, and Louise.

Susie Boss and her husband Sam Walker had a daughter, Kitty. Kitty and her husband, Angus McLeod, lived at Lower Laberge for many years. Angus was from Scotland and worked as a deckhand5 on the boats and ran mail to Livingstone by dog team in the winter. In the 1920s, Angus and Kitty, with other Ta'an people, operated a fox and mink ranch at Lur dayel ( 31 Mile) the home of Mundessa until his death in 1925.6

Jenny Smith Laberge's name was Hu ala, from Klukwan,7 Alaska. Her husband, Laberge

Billy, (also known as Billy Laberge) was K'umgaelte. He was born and raised along the Hootalinqua River at Winter Crossing near Livingstone. He was Gertie Tom's grandmother's brother.10 Billy Laberge died in June 1939 at about age 60.

Jenny Laberge and Laberge Billy had their base camp at Winter Crossing on the Teslin River. Eventually they settled and raised their family in Whitehorse. Jenny had nine children: Peter, Amy, Pauline (Polly Irvine),8 Mary, Sadie, Violet (Storer), Harold, Elizabeth and Peter. Amy and her husband, William (Bill) James Clethero, (spelled by some family members as Cletheroe)9 were among the first to mine in the Livingstone Creek area, along with "Dutch" Henry Broeren. Other Ta'an families also sometimes joined in mining operations.10 (For more on the Clethero family, see Biographies section.)

Elsie Baker Suits at gravesite of her mother, Sadie Jackie Baker, Livingstone Creek, 1995.

May Suits Getz fond YA 2002/133 #1

Also resident at Winter Crossing were "Big Salmon Pat", and Charles (Charlie) Smith and his married family, who were known as "Mackintosh".11 Elsie Suits mentions Charlie Smith living at Mason’s Landing.12 Charles Smith and Field Smith served Livingstone Creek as hunters, selling wild meat (see additional notes, below). Kitty Smith’s father delivered mail to Livingstone, and told stories of a Christmas party there.13

Marsh Lake Jackie, a chief, and Mary Lilly were direct ancestors of the Baker family who lived at the Boswell and Mary rivers, homesteading, trapping, and mining. Sadie Jackie and Jim Baker raised their children there, and also spent time mining at Cottoneva

Creek. Mike Murphy and Louie Keise were Baker’s mining partners. Sadie died at

Cottoneva at age 30 in 1919 and is buried on a hillside above the Livingstone townsite.14

Frank Slim, the only First Nations river boat pilot to be fully licensed, lived in the Baker Lake, Winter Crossing and Livingstone Creek areas. For a time he lived in what is known as the Trapper’s Cabin at Livingstone, and appeared to have sold trapping supplies from there.15 According to Elsie Suits, he used to stay at Baker Lake for the winter to protect the place against theft.16 (See also BIOGRAPHY section of this report).

Dorothy Baker Webber, daughter of Sadie Jackie Baker, Boswell River, 1934

William Webber fonds, YA 1002/134 #2

Additional notes ↑

The First Nation population at Livingstone Creek was 15 in 1904. From 75 to 90 persons were employed at mining in the Livingstone Creek district in the summer of 1904.17

Found with papers belonging to Louis Engle at Livingstone Creek were cheque stubs with dates ranging from November 5th 1934 - October 23 1942. These included cheques to Frankie Jim and Field Smith for meat, and to Charlie Smith & Chas Smith for moose skin & meat.

From the “Accounts of Percy Sharpe” found at Livingstone is the following note: Mcginty

[McGinty] Indian, Gld Standing 1931, In Account with J.E. Peters, "Mr. Peters gives No Detail: $2".18

First Nations Traditional Territories, Livingstone & Laberge area.

A Summary History Of Livingstone Creek, YT, 1897-1930 ↑

Adapted from an original report by Gordon Bennett, post-1973

Note: The following is modified from a staff report written by Gordon Bennett for Parks Canada in the 1970s.19 Subtitles, photos, maps, and further notes (appended as footnotes a,b,c etc) have been added. Mr. Bennett’s Endnotes, as in the original, are at the end of the article. Because some passages have been rearranged, not all Endnotes are in sequence, but the numbers correspond to the appropriate notes.

A Summary History of Livingstone Creek, Y.T. ↑

1897-1930

Prelude ↑

The gold rush of 1897-98 is commonly associated with the stampede to the Klondike and the spectacular rise of the town of Dawson.

Less well known is that there was a corollary if not corresponding series of smaller stampedes from Dawson to other regions in the Yukon, impelled by the discovery that most of the gold-bearing gravels in the Klondike had already been staked before the second great wave of stampeders hit Dawson in May and June of 1898. As early as mid-August of that year the Yukon's first commissioner, James M. Walsh, reported that upwards of five thousand people had left Dawson for the Stewart River country.1 Nor was the Stewart the only region to attract gold seekers whose Klondike aspirations had been frustrated.

"A great many people also went up the Pelly, Little Salmon and Big Salmon rivers," Walsh wrote, "but no reliable reports have yet been received as to what prospects have been found in these localities." 2

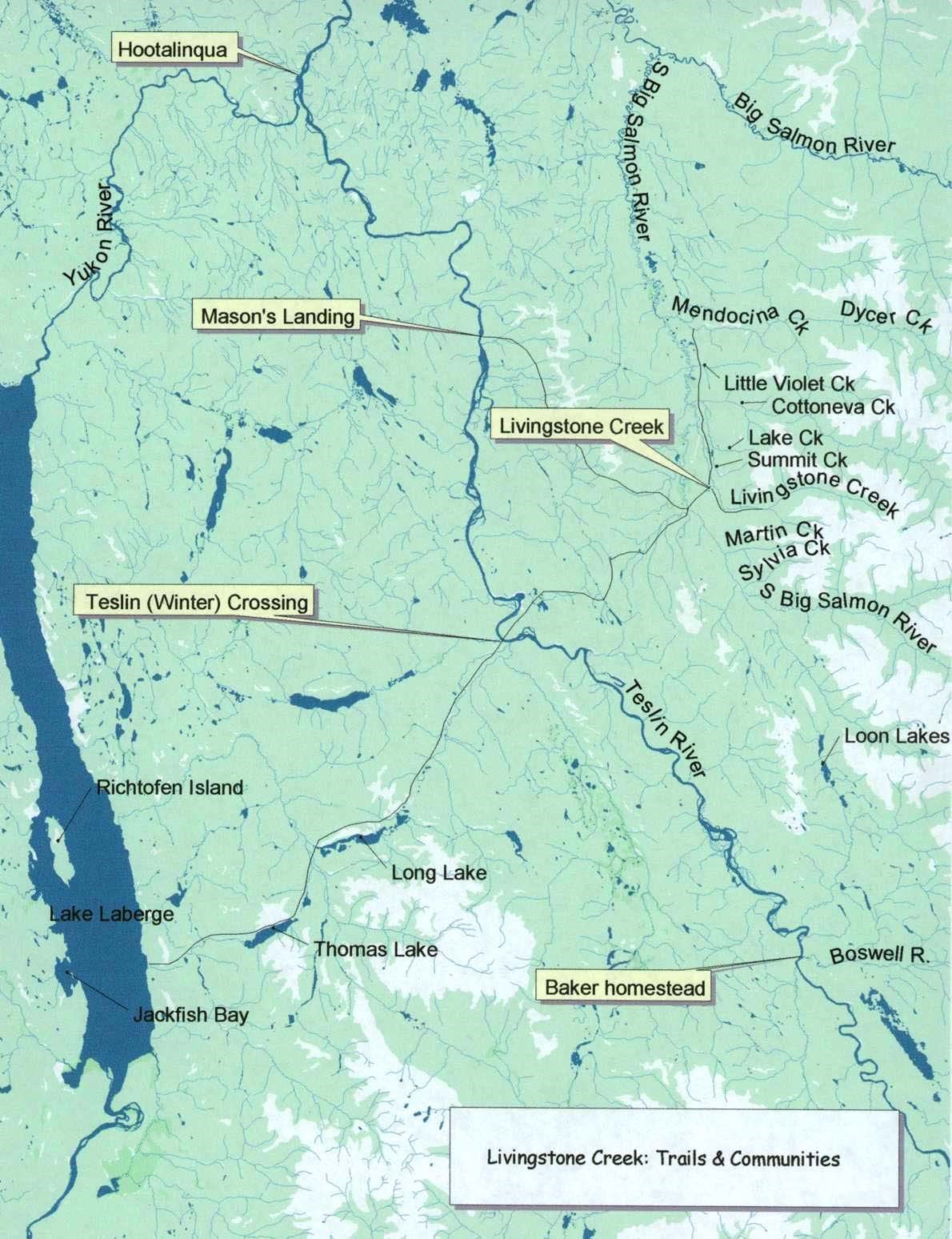

A year later, gold was discovered on a small tributary of the South Fork of the Big Salmon River, Livingstone Creek (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 (Map provided by HRU)

Discovery ↑

The discovery of gold on Livingstone Creek is generally credited to George Black20 and Samuel Lough.3c For the former, the discovery presaged a career that would culminate in the Speaker's chair in the House of Commons, for the latter it meant temporary recognition and subsequent obscurity.

More relevant to the history of Livingstone Creek is that the discovery followed the pattern described by Walsh; for after weeks of unsuccessful travail in the Klondike gold field (Black later wrote that he did not find "a colour of dust") Black abandoned the Klondike for the Teslin River-Big Salmon region. For almost a year Black operated out of his base camp at Hootalinqua before he and Lough discovered pay on Livingstone Creek. According to a contemporary issue of the White Horse Star, Black and Lough took out $3,600 from their claims in 1899. "No Bonanza, to be sure," admitted Black, but enough to repay "us well for two years of unremitting toil and hardship."4

Mining Activities 1892-1902 ↑

From the beginning, Livingstone Creek was not a "poor man's" camp. This fact predisposed a course of development for Livingstone Creek that differed in many respects from the pattern if not the outcome of development in the Klondike.

Although the Livingstone Creek diggings were blessed with a high assay value, a stream with a steep gradient (150 feet to the mile) and a more than adequate supply of timber and water (a crucial requirement for placer mining in the Yukon), it was evident as early as 1900 "that hand labour would not pay and that some form of machinery was required to put the claims on a paying basis."5

There were several reasons. for this. Much of the ground on Livingstone Creek, unlike the Klondike, was not frozen.6 While this eliminated the need for thawing it meant that cribbing was required for all drifts and tunnels.7 In contrast to the Klondike again, water was plentiful - so plentiful, however, that shafts were continuously flooded thereby necessitating the installation of pumps and the sacrifice of "a claim or so" on the creek in order "to get a drain to bedrock." 8

Large boulders, some of which measured six to eight feet in diameter hampered operations on the canyon portion of the creek and required costly hoisting apparatus although in this instance the water supply was used to advantage as a power source for the derricks.9

Finally, mining was "practically all open cut work" using hydraulic monitors and could be more efficiently prosecuted on a series of claims rather than individual ones.10 Taken together, these factors deterred the smaller operator who lacked capital except in so far as he was willing to work for wages.

Some indication of the problem encountered by the smaller operator is given by A. Acland, the corporal in charge of the detachment at Livingstone Creek, in his report for 1901.

"A large number of claims recorded in this district have not had a shovel turned in them this season," he wrote, since "the owners were either out of the country, working day labour for other parties or prospecting for easier creeks to work."11

One of these creeks was Lake Creek, two miles below Livingstone, but as J.T. Lithgow, the territorial comptroller, wrote, "the stakers [on Lake Creek] consist of persons who desire to hold claims and await developments and are not us a rule actual miners.”12

Such was also the case on Livingstone Creek where Corporal Acland predicted "that the properties worth holding will eventually pass into the hands of larger operators, until which time very little can be looked for."13

Although the census of April 1900 showed 84 people on Livingstone Creek the only claim that could be called a producer was J.E. Peter's lower discovery which yielded $10,000 in 1900 and $7,193.56 in 1901.14

On 2 June 1900 creek claims one to ten below discovery were sold at crown auction in Dawson.15 These claims were acquired by the Livingstone Creek Syndicate.16 The syndicate spent most of 1901 preparing for the 1902 season and several tons of machinery were brought in that winter.17 The company employed six to 12 men through the summer of 1902 but the diggings did not advance beyond the development stage, discovery claim still proving to be the only steady producer.18

Despite this apparent lack of progress, production declined in 1901 and remained static in 1902. Assistant Commissioner I.T. Wood's report on the 1902 season was that the "claim owners seem to be very well satisfied with the prospects.”19 Although the years 1900 to 1902 were not conspicuous in terms of production the camp made steady if unspectacular progress.

To draw a parallel with the Klondike it can be said that the nature of the Livingstone Creek placers forced a transition in the methods of mining at a very early stage in the life of the camp and that this transition preceded and anticipated the conversion to capital intensive mining that took place in the Klondike after 1903.20 As was the case in the Klondike, this transition was marked by a decline and then a leveling off of production until the new mining methods had pretty well replaced more primitive types of mining technique, after which production revived.21

Transportation ↑

In the meantime, the camp steadily improved its transportation links with Whitehorse, its principal supply centre. Although Livingstone Creek was part of the Big Salmon River system, the camp relied on the Teslin or Hootalinqua River for access to Whitehorse during the navigation season. In part, this was a consequence of the difficulty of navigating the Big Salmon.22

Probably more important, however, was the fact that Hootalinqua, located at the confluence of the Teslin and Yukon rivers, was 30 miles closer to Livingstone Creek than the post at Big Salmon, and was the site of the closest mining Recorder Office as well.23

By 1901 the miners had blazed a pack trail between Mason's Landing on the east side of the Teslin River and the South Fork of the Big Salmon, a distance of 15 miles, and constructed a rude bridge over the South Fork from which branch trails led to the various creeks in the district.24 That this primitive transportation route was not satisfactory is apparent from a comment made by Assistant Commissioner Wood.

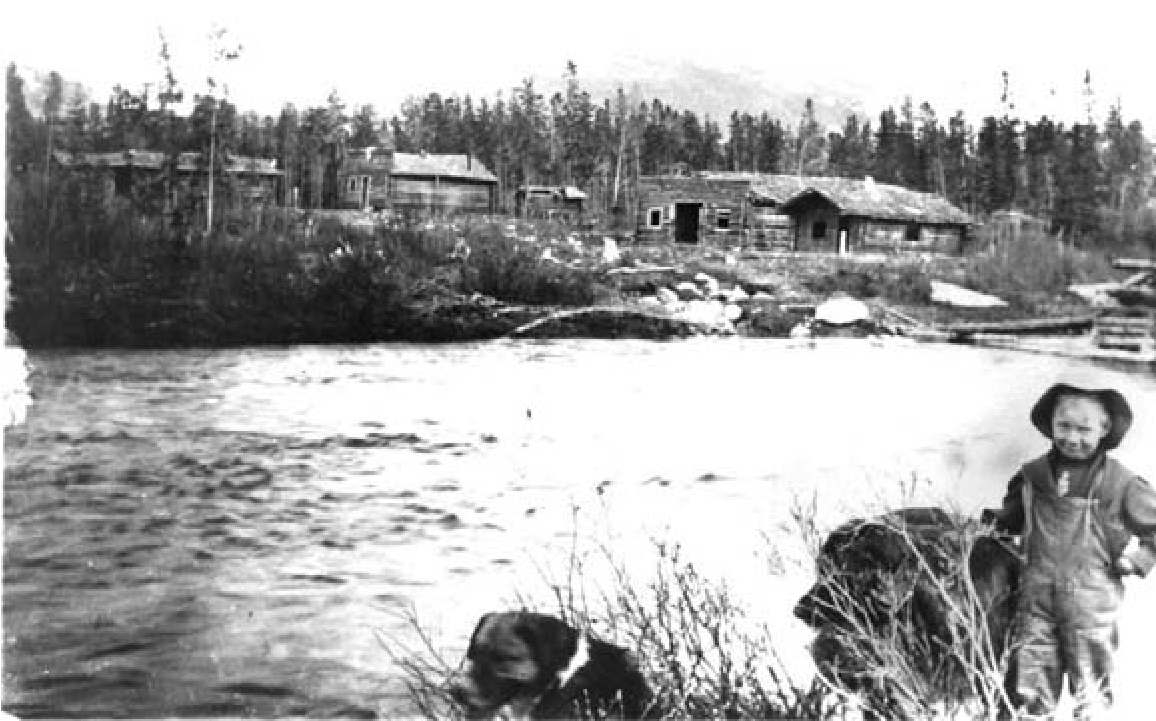

Mason's Landing, Blick child YA2002-132 # 48, Pearl Keenan Coll.

"One thing has however kept this district back," he wrote, "and that has been the cost of necessaries, as freight from Eureka Landing [one mile south of Mason's' Landing on the left limit of the Teslin River] to the gold bearing creeks has cost 8 cents a pound; this added to the charge of freight from Whitehorse, 1½ cents a pound, made the cost of provisions, & etc, so high that only fairly rich claims have been worked at a profit."25

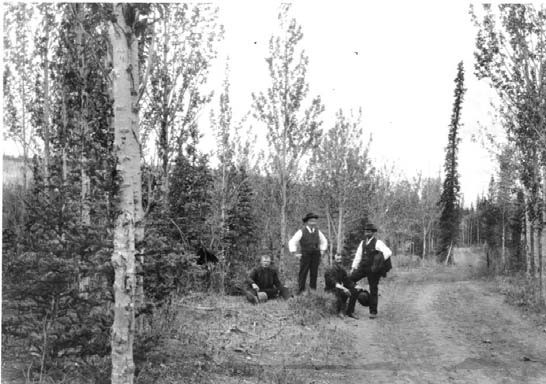

Men on Wagon Road to Mine YA2002-132-39 Pearl Keenan Coll.

In response to demands for a wagon road between Mason's Landing and Livingstone Creek the government constructed a 16 mile wagon road at a cost of $1,700 between Mason’s Landing and No. 10 claim below discovery on Livingstone Creek in 1902.26 Although some of the miners complained that the road was poorly located, an investigation revealed that most of the inhabitants were satisfied.27 Their satisfaction is understandable when the reduction in freight rates, that followed the road's construction is taken into account. According to Acland, the new road constituted "a saving- of $3,066 per year in provisions alone," and "half as much more [again] on... tools, machinery, clothing and general supplies, thus making a total saving per year in round figures of $4,500," for the settlement.28

The matter of summer land communication with Mason's Landing had no sooner been disposed of when Corporal Acland advised that "a winter trail to White Horse is urgently needed here, via the head of Lake LaBarge [Laberge]."29 Because the rivers were frozen over during the winter, and because the river route from Mason's Landing resembled a switch-back, a much more direct route was desirable. During the winter of 1901-02 the miners roughed out a "makeshift" winter trail to Upper Laberge, and this was improved to a "fair one-horse trail" by the North-West Mounted Police and the miners the following year.30

THE QUICK, Freighting To Livingstone, Teslin River YA2002-132 #80

Surprisingly, the one element in the transportation system that proved most difficult to improve was steamer connection between Whitehorse and Mason's Landing. The British Yukon Navigation Company’s S.S. Bailey made occasional trips to Mason's Landing in 1901, but the company refused to give regularly scheduled service.31 This was a source of great irritation to the residents of Livingstone Creek since no one knew when supplies, especially perishables, would be delivered and few people were interested in making the round trip of 32 miles to the Landing on the off-chance of catching a riverboat.

The situation was exacerbated, moreover, by the British Yukon Navigation Company policy of eliminating all common carrier competition in order to gain a transport monopoly on the upper Yukon River, and this discouraged the miners themselves from operating a boat as they were afraid if one were placed on, the B.Y.N. would then put on a boat, with freight rates that would drive the private boat out of business."32

With its achievement of a practical monopoly, on the most important waterways by 1900, the British Yukon Navigation Company abandoned its concern with the economically marginal side streams trade and in that year Thomas Smith of Whitehorse began running on the Teslin River with the tiny S.S. Quick, thereafter supplying Livingstone Creek with the bulk of its supplies.33

Mining Activities 1903-1915 ↑

The year 1903 established Livingstone Creek as an important gold producer and commentators reflected on the fact that the creek was finally "beginning to make some return" for the considerable expenditures of labour and capital of the previous three years. The Livingstone Creek Syndicate employed fifteen men through the summer and realized a. profit of $20,000. All told, the creek produced $100,000.34

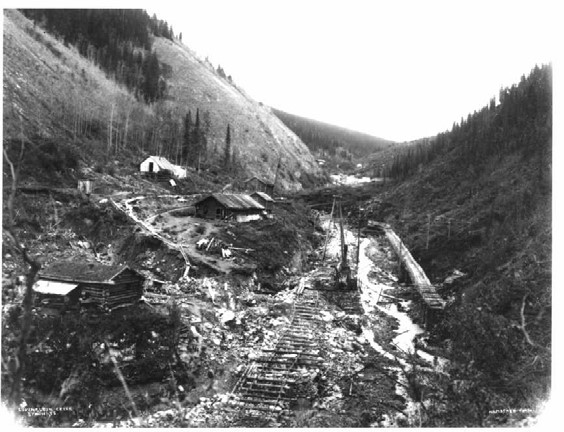

Livingston Creek Syndicate YA2002-118 # 338 Hamacher Coll.

A short working season in 1904, caused by a late spring and early frost, resulted in a decline of $40,000 in the camp's output compared with the previous year. Even more disconcerting was that only a few claims continued to yield pay, it being estimated that only two claims other than those worked by the syndicate produced gold in 1904.35 Although production reached its 1903 level of $100,000 in 1905, $76,000 of this was taken out of two claims.36

The discovery of a new pay streak in the old creek channel on the left limit of the creek in 1905 raised the hopes of the operators but did not result in increased productivity. Output fluctuated between $35,000 and $100,000 a year until 1910 when the camp entered a period of protracted decline.37

Two types of ground were worked on Livingstone Creek, the bar diggings on the creekbed and the "old channel" on the left limit hillside. Little if any mining appears to have been done below upper discovery on the hillside which was located just below the head of the canyon. Operations on the creekbed covered a larger field, extending from lower discovery at the head of the canyon for some distance above, and through the three-quarter mile long canyon into the valley portion of the creek below. With two notable exceptions, the creek claims below discovery were hydraulicked or ground sluiced and the claims above discovery were worked with adits and drifts, as were the bench or hillside claims. The two exceptions were

creek claims 10 to 18 above discovery which were hydraulicked, and some claims below discovery where drifting was attempted in 1900 but forsaken when the shafts flooded (at a depth of 70 feet) before reaching bedrock.38

By 1908 mining was confined to creek claims 10 below to 18 above on the creek and upper discovery to 9 above on the hill.39 The Livingstone Creek Syndicate appears to have abandoned hydraulicing for drifting in 1909, and operations entirely after that season.40 Because water was needed to work the deposits extractive operations were primarily confined to the summer months and many of the miners appear to have spent the winters elsewhere.41

Livingston Creek Syndicate YA2002-118 # 348 Hamacher Coll.

A change seems to have occurred in 1909, however, for the agent to the mining recorder's report for that year states that "the bulk of the mining....is carried on the year round." This may have been the result of the predicted demise of the camp - the same agent wrote that "the miners here agree that the known ground on Livingstone Creek will be about all worked out next year” – and the operators may have wished to retire their diggings as quickly as possible.42

Another possible explanation is that operations were severely curtailed during the summer of 1909 by heavy rainfall, it being reported that "the incessant rains of the present season practically put a number of miners on Livingstone Creek out of business as far as accomplishing anything in the way of mining."43

Comparison of Livingstone with other mining communities ↑

Unlike its more famous counterpart, Dawson, the town of Livingstone Creek bore little resemblance to the gold rush camps that have become an integral part of the literature of the northwest. If anything, Livingstone Creek more closely resembled the isolated outpost settlements described by C.A. Dawson in his study of the Peace River frontier.44

Because mining required a good deal more capital than the average stampeder or prospector possessed, the Livingstone Creek diggings did not attract the type of settler synonymous with Barkerville, Forty Mile, Circle City and Dawson.

Corporal Acland captured the ambience of the community succinctly when he wrote that "the general tone has been good, nearly all the inhabitants being hard-working, industrious people, and the camp is not rich enough to attract the riff-raff which usually follow mining camps."45

Unlike the Klondike gold field, where bitterness between capital and labour was a commonplace until the passage of lien laws, there were "no differences between employers and employees among the miners" at Livingstone Creek.46 Nor was there the organized and vociferous opposition to capital that marked the Klondike field between 1902 and 1906-07.

To summarize, it can be said that there was no collision between the forces of metropolitanism and the values of the frontier on Livingstone Creek.

North-West Mounted Police post and population numbers ↑

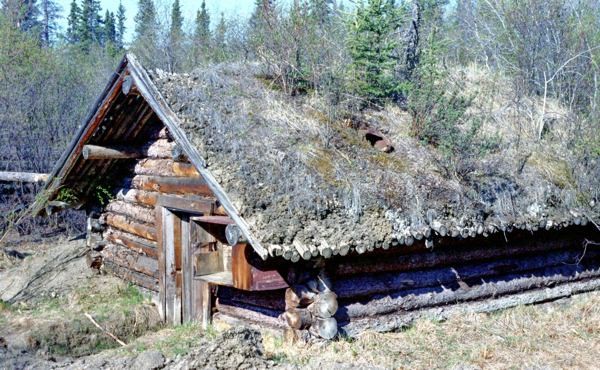

The post (see Figs: 3 & 4), was built in 1901 "owing to the great influx of people into the Big Salmon district."55 It consisted of three buildings: a barrack, kitchen and office building measuring 30' x 18', a storehouse (12' x 14') and a combination stable and doghouse (12' x 18'). The main building was made of lumber and had a board floor and mud roof.53 The buildings straddled the wagon road and were located approximately 150 yards south of the creek.

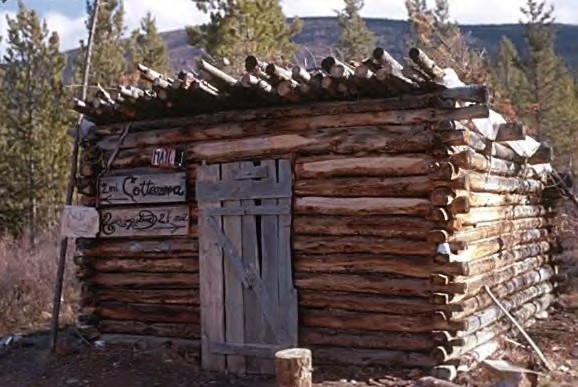

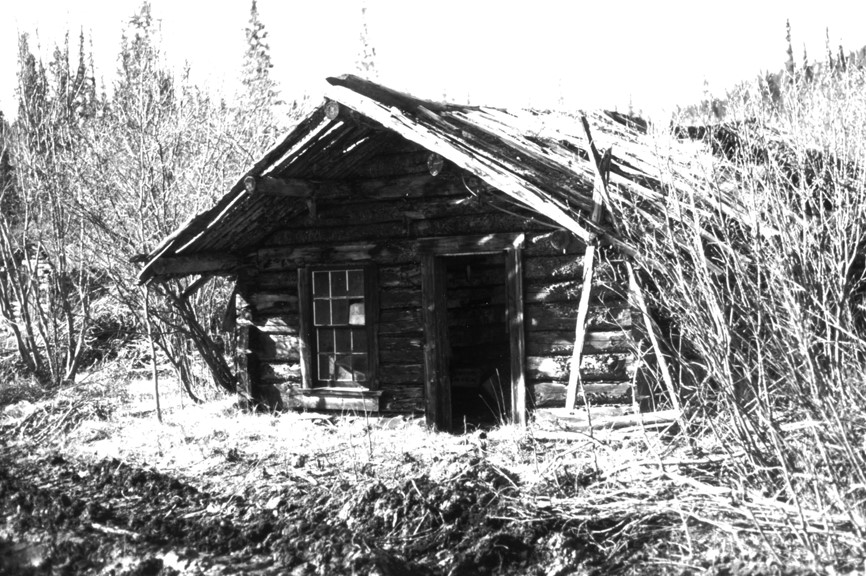

Fig. 3 N.W.M.P. Cabin, HRU 1980

The duties of the men of the detachment involved very little law enforcement but many activities that supported the miners. The officers discovered "that the best of feeling prevails here between the police and miners," and found that most of their work involved patrols and bringing in mail, while the N.C.O. in charge of the detachment took affidavits, issued free miners’ certificates and acted as sub-mining recorder and crown timber and land agent, tasks with the exception of the first, that were properly the responsibility of other government departments.

The N.C.O. was relieved of his nonpolice duties in 1903 when the Department of the Interior moved the mining Recorder Office from Hootalinqua to Livingstone Creek, but these duties were re-assigned in 1905 when the Department of the Interior closed the office part of a general policy of retrenchment.47

Fig. 4 NWMP Jail, HRU 1980

Although consistent population figures are not available, the population of Livingstone and surrounding creeks appears to have fluctuated between 60 and 125 for the period 1900-1910.56 In 1907, an average year for the camp in terms of production, a resident estimated the summer population at 100 and a winter population of 35 to 50 exclusive of children.57

The North-West Mounted Police considered withdrawing the detachment for the winter months as early as 1906, giving the reason that "there will not be sufficient people there to justify maintaining Police.” However, the post was not withdrawn since "the noncommissioned officer in charge is acting as agent to the mining recorder and Crown timber and land agent [and that] compel[s] us to keep open a post which would otherwise be closed until the residents of the creeks returned in March.58

With the decline in population after 1908, and evidence that the creek had been "pretty well worked out" by 1910, however, the detachment was permanently withdrawn during the winter of 1910 -11.59 For the next two years the camp was visited by police patrols but there is no mention of patrols being made into the area after 1912.60

Livingstone Town ↑

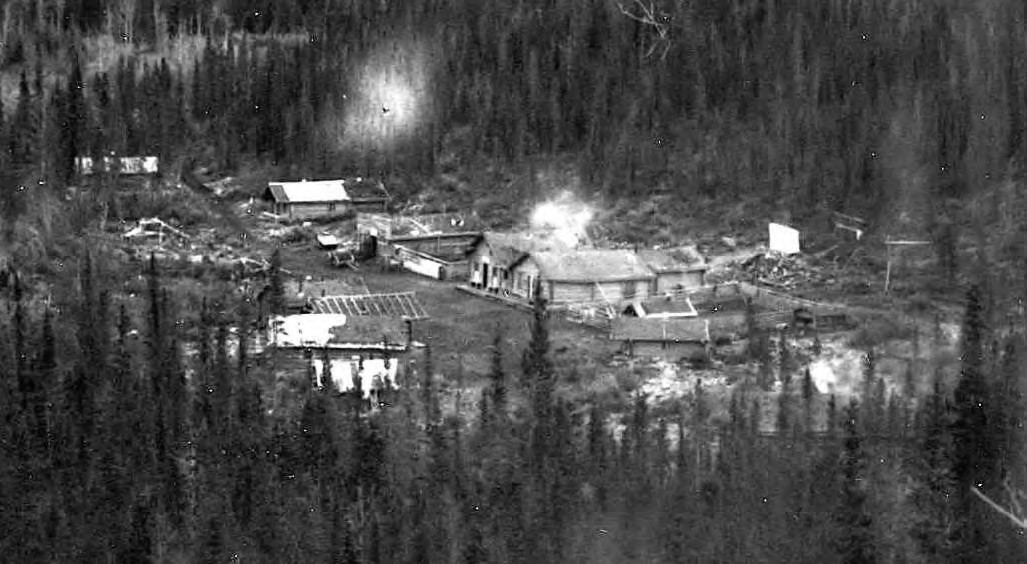

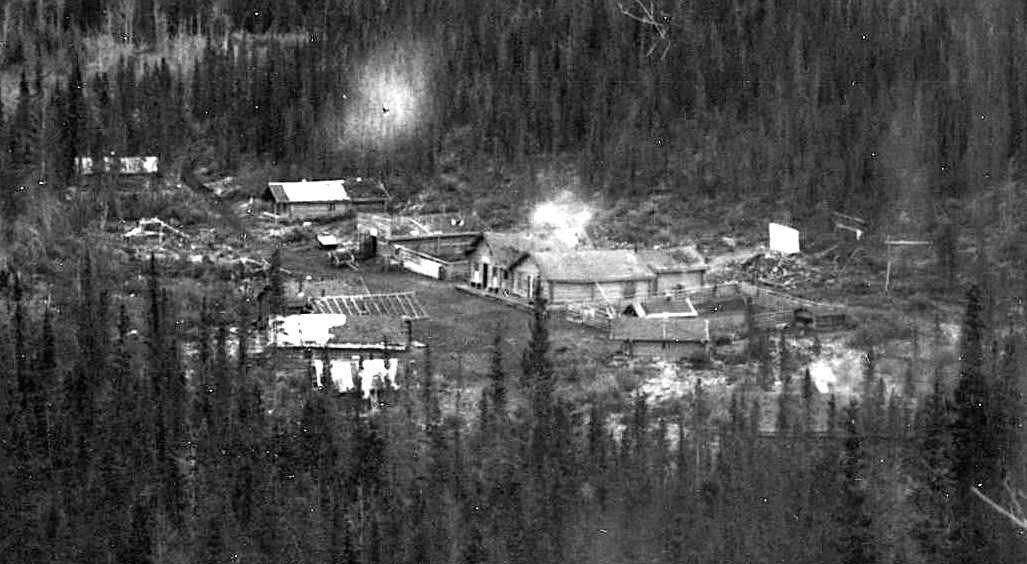

Livingstone Creek ca. 1906, YA 2002-1-118 #349, E.J. Hamacher fonds

The town of Livingstone Creek was the supply and administrative centre for what was known as the Livingstone Creek district. The district included several small creeks running from east to west into the South Fork of the Big Salmon River: Mendocino, Little Violet, Cottoneva, Lake and Summit creeks to the north; and Martin and Sylvia creeks to the south of Livingstone Creek (see Fig. 1). Placer operations were conducted on each of these creeks, although none matched Livingstone Creek as a gold producer. In his report for 1902, Corporal Acland noted two licensed and two unlicensed roadhouses as well as a general store in the district.51

The town itself, located some two to four miles above the mouth of the creek in a "Z" shaped, bend in the water course, contained a number of substantial log structure built along the wagon road from Mason's Landing.52

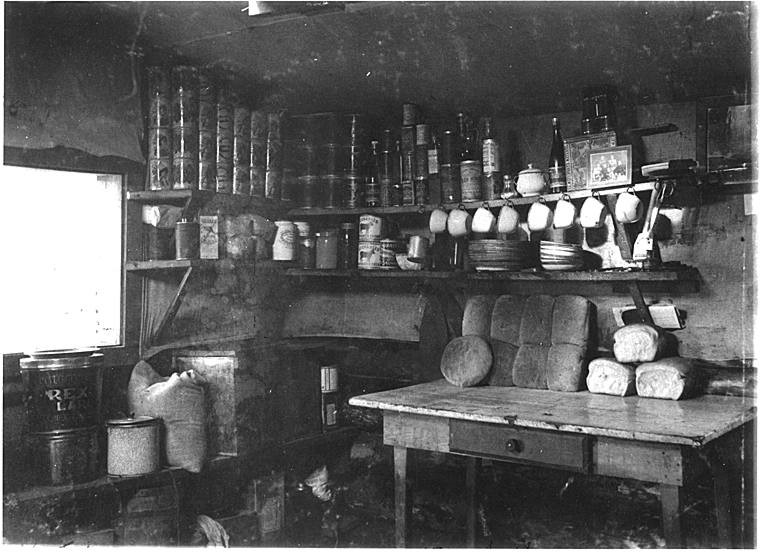

Dan Snure’s Place YA2002-118 # 155 E.J. Hamacher

Coll.

Daniel Snure,21 who had previously operated a roadhouse at Hootalinqua, followed the miners to Livingstone Creek where he established a "hotel" (roadhouse). If anyone can be said to have been Livingstone Creek's first citizen Snure was it, for in addition to owning the roadhouse he retailed general merchandise, owned mining claims, served as the community's one and only

postmaster, was the local Dominion telegraph agent (a telegraph line was put in in 1907) and served as agent to the mining recorder from 1910, when the Royal Northwest Mounted Police detachment was withdrawn, until 1925.54

Kitchen in Dan Snores (sic) Road House YA83-77 H247 PHO 232#59

A post office was finally established in 1908 after a long campaign for regular postal service, the miners having "themselves borne the expense of a messanger (sic) to carry the mail at a very heavy cost" since 1905.48

Mail delivery continued to be a problem, however. In 1912 George Ameroux [Aimraux] one of the largest operators on Livingstone Creek complained that the contractor, Thomas Smith, the owner of the Quick, was leaving the mail at Mason's Landing, "hanging in a tree... exposed to the weather and when delivered on the creek some of the letters and papers are so wet and mutilated they could not be read.”49 Complaints were registered at varying intervals between 1912 and 1914 until the post office was closed in 1915.50

Mining Activities 1911-1925 ↑

An indication of Livingstone Creeks’ diminishing importance after 1910 is that references to the district become a good deal more scanty. The population levelled off at about 30 and operations were continued on a much reduced scale.61

Snure's return for 1911 mentions that claim number 21 to 26 below discovery were being worked by the International Mining Company, but the company does not appear to have enjoyed very much success.62

The annual report of the Department of the Interior for 1912 stated that "Livingstone creek and tributaries have been unusually quiet throughout the year,"63 and this condition appears to have prevailed through 1914.64

The discovery of a new paystreak on an old claim in 1915 raised the hopes of the miners but these hopes were not sustained by the following year's returns.65

It is impossible to determine whether the recurring theme through these years that "the miners have absolute faith in the existence of gold in paying quantities" constitutes an embellishment on the part of authors of various official reports or an inaccurate reflection of miners' sentiment.66

In any event, output must have put that faith to a very severe test. In what looks to be an attempt to find some reason, any reason, beside the obvious one of exhaustion, difficulties were attributed to the war and the related problems of capital accessibility and the availability of labour.67 While these two factors had a significant impact on production in the Klondike, they were not important considerations on Livingstone Creek, however.

Production for 1916 and 1917, two years for which statistics are available, was 546.39 ounces and 485.97 ounces respectively, making, a total output of 8,195.85 in 1916 (distributed among 26 miners) and $7,289.55 in 1917 at a valuation of $15 an ounce.68 No figures are available for subsequent years, production being variously described as "very low" or "very small."69

After 1920 mining per se appears to have given way to prospecting in the Livingstone Creek area. Although this does not mean that production ceased, it does suggest a reversion to the earliest stage the mining process where diggings are worked in the hope of making a strike but where the prospector is satisfied so long as he can sustain a marginal if not meager existence. This denouement was not peculiar to Livingstone Creek; it does, in fact, constitute part of the typical life-span of most placer camps.

During the 1920s no more than six or seven men appear to have carried on operations in the district and no one seems to have been appointed local agent to the mining recorder after Snure resigned in 1925.70

In 1928 Richmond Yukon Copper Limited, which had taken over the Whitehorse copper properties, was granted a lease of two miles of ground on Livingstone Creek but the company did no work and its lease was not renewed.71 Two years later (1930) the same company took out 200 ounces of gold on a bench on Lake Creek but although it was predicted that this would have a salutary effect on mining in the region nothing appears to have happened.72

Demise of Livingstone Creek 1930s ↑

The passing from the scene of an outpost on the frontier is seldom if ever proclaimed. When that outpost is on the mining frontier it becomes even more difficult to date its final demise. Wherever there are prospectors of the "old school”, as there were in the Yukon during the 1920s and 30s, some of them are bound to be in a fringe region panning various creeks in the hope of making a new discovery. What is clear, however, is that by the mid-1930s, the once active camp at Livingstone Creek had long since passed into history, and a revised map published by the Department of the Interior in 1936 designates only a "shelter cabin" at Livingstone Creek.22

Apart from its importance in a very localized sense as a community where people lived and worked, the origins of the camp at Livingstone Creek represent an aspect of Yukon history that has not attracted very much attention. For just as the discovery of gold on Bonanza Creek in August of 1896 led to the Klondike stampede, so did that stampede spawn a series of smaller rushes to the outlying portions of the territory. The phenomenon described by the American writer, Rex Beach, that the short-lived nature of placer camps like the Klondike "very largely accounts for the headlong stampedes that were a characteristic feature of Alaska's development and which resulted in such rapid exploration of the country," also occurred in the Yukon and found expression in the establishment of settlements like Livingstone Creek.73

On a smaller canvas, Livingstone Creek, along with the Kluane field, was the most important producer of placer gold in a region (the Whitehorse mining division) where lode mining otherwise predominated. It has been estimated that Livingstone and surrounding creeks yielded something in excess of $1,000,000 worth of gold, the largest portion of which was taken out between 1900 and 1910.74 Because no records were kept of production from various creeks it is impossible to verify this figure. More likely it was closer to $750,000.75

Judged strictly in terms of production, there seems no reason to revise the early

(1901) assessment of the government geologist, R.G. McConnell, that the Livingstone "field can only be considered of moderate richness."76 Of the estimated total of $250,000,000 in gold won from the Yukon's placers, Livingstone Creek's share was 0.4 percent.

Closing notes ↑

Gordon Bennett’s report was written post-1973 but does not include the revival that began in 1971, peaked in the 1990s, and continues in some measure to the present. For gold productions figures for that period, consult the Mining Recorder Office in Whitehorse. The town of Livingstone was reoccupied at intervals by varying numbers of people from 1972, and during that time served again as a social hub for the outlying creeks. By 2003 the village had not been occupied for some years, and most of the buildings have succumbed to creek flooding and age. For a summary of this period see the Serafinchon account, Time Spent At Livingstone Creek (1971–1986) and the Fuerstner Family (1974 to present)23 in the Biographies section. Bennett’s history also does not mention the airstrip. See Aviation History.

Endnotes ↑

Canada. Department of the Interior, Annual Report, 1898 (Ottawa: Queen's Printer, 1F;99) (hereafter cited as CDI, Annual Report [appropriate year]), Pt. IV, P. 329.

Ibid., p. 330.

Dawson Daily News, Special Edition, 21 July 1909, p. 72; Canada. Public Archives hereafter cited as PAC), Martha Black Papers, MG 30, H43, "To the Electors of the Yukon," a. pamphlet distributed by the supporters of George Black in the 1930 federal election; George Black, "striking Gold in Klondyke Was My Finest Hour," John Bull, 24 Dec. 1932, p. 22. Two discovery claims were registered on Livingstone; one on the hillside called upper discovery, and one on the creek known as lower discovery. Records available to the writer in Ottawa do not indicate whether Black and-Lough located on the upper or lower discovery claim, or which claim was the first to be recorded. It is known, however, that some of the claims applied for by Black were hillside claims. See PAC, Records of the Northern Administrations Branch, RG 85, Box 1420, fol. 24119. The Mining Recorder Office in Whitehorse should have a bound volume on Livingstone Creek listing all claims and transactions.

Reconstructed from George Black, op. cit., p.22. Allowing for minor mistakes in dating and a disconcerting disregard for geographical accuracy, this article is the only first person account extant of the Livingstone Creek discovery. The production figure is from the White Horse Star, First Annual Edition, 1901, 1 May 1901, p. 14. See also PAC, RG 85, op. cit., which places Black in the Hootalinqua region and describes the problems Black had in recording his claims.

H. Bostock, comp. Yukon Territory: Selected Field Reports of the Geological Survey of Canada, 1898-1933, the Geological Survey of Canada, Memoir 284.

(Ottawa: King's Printer, 1957), p.39; , Annual Report of the Commissioner, 1901 (Ottawa, King's Printer, 1902) (hereafter cited as NWMP [after 1903, RNWMP], Annual Report [appropriate year?], Pt. III, p. 30; PAC, RG 85, Box, 1437 fol. 144190, Beaudette to Acting Commissioner, Dawson, 18 July 1907; CDI, Annual Report, 1901, p. 30.

H. Bostock, op. cit., Pp. 40, 623-4.

See PAC, RG 85, Box, 1424, fol. 32198, Corneil to Gold Commissioner, Livingstone Creek, 20 Jan. 1909, which describes operations on Livingstone Creek.

H. Bostock, op. cit., p. 40; NWMP, Annual Report, 1900 Pt. III, PP. 30-1; ibid., 1903, Pt. III, p. 34.

NWMP, Annual Report,_ 1903, Pt. III, P. 34; H. Bostock, op. cit., P. 39.

NWMP, Annual Report, 1903, Pt. III, p. 34.

Ibid.

PAC, RG 85, Box 1419, fol. 22585, Lithgow to Ross, Dawson, 30 July 1901.

NWMP, Annual Report, 1902, Pt. III, p. 51.

Ibid., 1900, Pt. III, pp. 30-1; ibid., 1901, Pt. III, p. 31,

Ibid., 1900, Pt. III, p. 31.

The syndicate may have been a subsidiary of the Alaska Commercial Company, see White Horse Star, First Annual Edition, 1901, 1 May 1901, p.

14. No record of it exists in Statutes of Canada, 1898-1905 or the Canada

Gazette for the same period. Under an amendment to the Companies Act of 13

June 1898 (61 Vict., Cap. 49) all companies with foreign charters (the Alaska

Commercial Company was an American company) wishing to mine in the

Yukon had to secure a license from the Secretary of State of Canada and

"notice of the issue of such license shall be published in the Canada Gazette" (Sect. 4 of the Act). As previously mentioned, however, no such notice was ever published for the Livingstone Creek Syndicate.

NWMP, Annual Report, 1901, Pt. III, p. 30. 18 Ibid., 1902, Pt. III, p. 30

Ibid., 1902, Pt. Iii, p. 51.

Ibid., 1901, Pt. III, p. 30; ibid., 1902, Pt. III, pp. 7, 51.

The annual reports of the North-West Mounted Police, which constitute thesource of information during this period, make reputed reference to the importation of heavy machinery and hydraulic plants between 1900 and 1902-03. Ibid., 1900, Pt. III, p. 7; ibid., 1901, Pt. III, p. 30; ibid., 1902, Pt. III, p: 7; ibid., 1903, Pt. III, P. 34.

See Canada, Dominion Bureau of Statistics, Chronological Record of Canadian Mining Events From 1604 to 1947 and Historical Tables of the Mineral Production of Canada Ottawa, King’s Printer, 1948, p. 92.

H. Bostock, op. Cit., p. 37.

CDI, Annual Report, 1909, Pt. VI, p. 29, Table 3. The first mining Recorder Office for the Big Salmon gold field was at Fort Selkirk. An office was opened at Hootalinqua circa 1900 and an office was established at Livingstone in the spring, of 1903 (PAC, RG 85, Box, 1420, fol. 24119 ibid., Box 1414, fol. 17194; ibid., Box 1417, fol. 203461.

H. Bostock, op. cit., p. 37; PAC, RG 85, Box 1419, fol. 22585, Lithgow to Ross, Dawson, 30 July 1901.

NWMP, Annual Report, 1902, Pt. III, p. 7.

Ibid.; White Horse Star First Annual Edition 1901, 1 May 1901, p. 14; PAC, RG. 5,

Box, 1419, fol. 2255, Lithgow to Ross, Dawson, 30 July 1901; CDI, Annual Report, 1902-03, Pt. IV, p. 26.

NWMP, Annual Report, 1902, Pt. III, p. 50. 28 Ibid., p. 52.

Ibid., p. 52.

Ibid.

Ibid.; 1903, Pt. III, p. 35. It is interesting to note that the winter trail resulted in the NWMP withdrawing its detachment from Hootalinqua for the winter after the fall of 1905 (ibid., 1905, Pt. II, p.8.

PAC, RG 85, Box 1419, fol. 22585, Lithgow to Ross, Dawson, 30 July 1901; NWMP, Annual Report, 1902, Pt III, pp. 52-3.

NWMP, Annual Report, 1902; Pt. III, pp. 52-3.

Ibid., 1907, Pt. III p. 22; Canada. Department of Marine and Fisheries List of Shipping 1908.(Ottawa: Ring's Printer, 1909, p. 124. Mention must also be made of the settlement of Commercial Centre (see Fig. 1) which various issues of Polk's Alaska-Yukon Gazetteer describe as the "commercial point for the Big Salmon mining district" (1903, 1905-06, 1917-18). The writer has found no reference to this community elsewhere, nor is it shown on either the 1903 or 1917 maps published by the Department of the Interior.

NWMP, Annual Report, 1903, Pt. III, PP. 19, 34.

Ibid., 1904, Pt. III, pp. 33-4. The syndicate worked Nos. 10 to 19 above discovery in 1904, in addition to its own claims.

Ibid., 1905, Pt. III, p. 41.

CDI, Annual Report, 1904-05, Pt. VIII, p.. 31; H. Bostock, op. cit., p. 243; PAC, RG 5, Box 1424, fol. 32198, Acland to Gold Commissioner, Livingstone Creek, 1 Jan. 1910; CDI, Annual. Report, 1909, Pt. VI, p. 16.

Dawson Daily News, Special Edition, 21 July 1909, p. 72; H. Bostock, op. cit., pp. 39-40; PAC, RG 85, Box 1424, fol. Y08, Corneil to Gold Commissioner, Livingstone Creek, 20 Jan. 1909.

PAC, RG 85, Box 1424, fol. 32198, Corneil to Gold Commissioner, Livingstone Creek, 20 Jan. 1909.

Ibid., Acland to Gold Commissioner, Livingstone Creek, 1 Jan. 1910. No mention of the syndicate is made in the reports of the agent of the mining recorder at Livingstone Creek after the 1909 season.

Ibid., Corneil to Gold Commissioner, Livingstone Creek, 20 Jan. 1909; NWMP, Annual Report, 1902, Pt. III, p. 7.

PAC, RG 85, Box 1424, fol. 32198, Acland to Gold Commissioner Livingstone Creek, 1 Jan. 1910.

RNWMP, Annual Report, 1909, Pt. III, p. 208. See also CDI, Annual Report, 1910, Pt. VI, p. 18.

C.A. Dawson and R.W. Murchie, The Settlement of the Peace River Country: A Study of. a Pioneer Area., Vol.6 of Canadian Frontiers of Settlement, eds. W.A. Mackintosh and W.L.G. Joerg Toronto: Macmillan, 1934, pp. 3-4.

NWMP, Annual Report, 1902, Pt. III, p. 53.

Ibid., 1906, Pt. III, p. 19.

Ibid.,1901, Pt. III, PP. 7, 9, 19; ibid., 1903, Pt. III, P. 35; ibid., 1905, Pt. III, p. 44; ibid., 1907, Pt. III, p. 22; PAC, RG75, Vol. 599,01. 2149, White to the secretary of the Department of the Interior, Ottawa, 15 Oct. 1906; ibid., Box 1417 fol. 20346, Wood to Smart, Dawson, 18 Nov. 1902. The closing of the Livingstone Creek office should not be considered an indicator of diminished status for Livingstone Creek. Offices on Bonanza, Hunker, Sulphur, Gold Run, Upper Dominion, Forty Mile, Glacier, Stewart River, and at Selkirk were closed concurrently (CDI, Annual Report, 1904-1905 Pt. VII, p. 5.

PAC, RG 85, PARC 426, "Memorandum re: mail service provided to Yukon District," n.d.; PAC, Yukon Territorial Records, RG 91 , Vol. 10, fol. 2093, Reel M-2835, Blick et al to the Postmaster General, Livingstone Creek, 6 July 1907.

PAC, RG 91, Vol. 10, fol. 2093, reel M-2835, Ameroux to Thompson, Dawson, 12 Oct. 1912. Ameroux,'s name is variously spelled -oux and -ioux.

Ibid.; PAC, RG 85, PARC 426, "Memorandum re: mail service provided to Yukon District," n.d.

NWMP, Annual Report, 1902, Pt. III, p. 51.

The figure "a dozen or more” is given in Bostock's 1921 field report (H. Bostock, op. sit., p. 62.0). However, a forest fire in 1920 destroyed several cabins (PAC, RG 85, Acc. 70/310, Box 6, file 4907, Berton to

Whitehorse, 5 Apr. 1921). It is presumed that the town was close to the NWMP detachment which is shown in Figs. 3 & 4. A map submitted to the department (Indian and Northern Affairs) in 1973 requesting that an historic reserve be placed on the creek shows the mining recorders office in the same general vicinity as the police compound. Figs. 5 & 6 show well-constructed log structures on each side of what was probably the wagon road [photos not available].

NWMP, Annual Report, 1901, Pt. III, p. 20; PAC, Royal Canadian Mounted Police Records, RG 18, Vol. 3087, "NWM Police Reserves in Yukon."

PAC, RG 85, Box. 1420, fol. 24119; Polk's Alaska-Yukon Gazetteer, 1915-

16, p. 780; PAC, RG 85, Box, 1424, fol. 32198, Corneil to Gold

Commissioner, Livingstone Creek, 20 Jan. 1909; PAC, RG 91, Vol. 10, fol.

2093; reel M2835, Lowe to Henderson, Dawson, 14 Aug. 1907; RWMP Annual Report, 1907, Pt. III, p. 6; PAC, RG 85, Acc. 68/130, Box 155739, fol. 62853, Keyes to Dawson Gold Commissioner, Ottawa, 6 Oct. 1910; PAC, RG 85 Vol. 659, Reid to Whitehorse Mining Recorder, Dawson, 2 July 1925.

Annual Report, 1901, Pt. III p.7.

Ibid., 1901 - 1910; CDI, Annual Report[s], 1901-1910

PAC, RG 91, Vol. 10, fol. 2093, reel M-2835, Blick et al to Postmaster General, Livingstone Creek, 6 July 1907.

PAC, RG 85, Vol. 599, fol. 2149, White to Secretary of the Department of the Interior, Ottawa, 15 Oct. 1906; RNWMP, Annual Report, 1906, Pt. III, p. 99.

RNWMP, Annual. Report, 1910, Pt. III, pp. 214, 224.

Ibid., 1911, Pt. III, p. 214; ibid., 1912, Pt. III, p. 224

Ibid., 1911, Pt. III, p. 221-2; Polk's Alaska Yukon Gazetteer, 1915-16, p. 80.

PAC, RG 85, Box 1424, fol. 32198

CDI, Annual Report, 1912, Pt. I, p. 80.

Ibid., 1914, Pt. I, p. 70-1.

RNWMP, Annual Report, 1915 Pt. III, p. 250; CDI, Annual Report, 1916, Pt. I, p.

62.

CDI, Annual Report, 1912, Pt I, p. 80; ibid., 1914, Pt. I, p. 70-1.

Ibid., 1917, Pt. I, p. 62.

PAC, RG 85, Acc. 70/310, Box 6, fol. 4907; Polk's Alaska Yukon Gazetteer, 191516, p. 70-1.

PAC, RG 85, Acc. 70/310, Box 6, fol. 4907; PAC RG 85,

Box 1431, fol. 48020, "Synopsis of Annual Report of Whitehorse Dominion Lands District, 1919."

PAC, RG 85, Acc. 70/310, Box 13, fol. 4907, "Report of the Whitehorse Mining recorder, 10 Apr. 1928," which gives a brief description on mining in the district between 1922 and 1927; ibid., 1929; PAC, RG 85, Vol. 659, fol. 3595.

PAC, RG 85, Acc. 70/310, Box 13, fol. 4907, "Annual Report for the Whitehorse Dominion Lands District, 31 Mar. 1930."

Ibid., Box 15, fol. 5659, "Mining Conditions in Yukon, 1930,"; ibid., "Mining Conditions... 1935."

Rex Beach, Personal Exposures (New York: Harper, c. 1940), p. 58.

H. Bostock, op. sit., p. 623.

See PAC, RG 85, Acc. 70/310, Box 6, fol. 4787, Rowatt to Self, Ottawa, 11 Feb. 1913. The writer's estimate is based on a study of production figures given in various years.

H. Bostock, op. sit., p. 41.

Aviation History of Livingstone Creek ↑

The following is drawn from the memories of Bob Cameron, Al Serafinchon, Lloyd Ryder, Gerry McCully, and the researcher. Other sources are as identified in the footnotes.

Aviation History of Livingstone Creek ↑

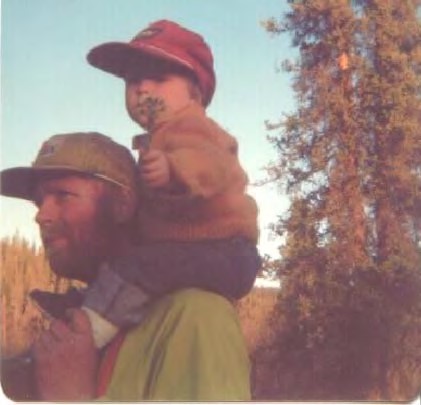

From the 1930s on, air travel has been an important part of supporting the mining and trapping activities of the Livingstone Creek district, transporting passengers and many tons of freight and gallons of fuel in all seasons, thus reducing dependence on the long, often impassable roads. It had a direct effect on the social life of the creeks by making it more possible for young children to be part of the isolated community (55 air miles, 70 miles by winter road from Whitehorse). Because they could be transported relatively swiftly to medical attention if needed, families were able to remain together throughout the mining season.

Ford Trimotor airplane at Livingstone Creek, May 1938, YA 82-322 PHO 26 #22, Norman Stone Coll. L. to R.: Taylor McGundy, Solomon Charlie,Co-pilot Buck Stone, Dan Snure, & unidentified “Livingstone Miners”. Pilot Ev Wasson below on same occasion.

The first landing field was a meadow

approximately one mile from South Fork (Big Salmon River), about three

miles west of the Livingstone townsite. Lloyd Ryder recounts, “That

runway was done by hand, pulled all the stumps and stuff with pry-poles.

It was in good condition. There were no Cats out there in the ‘30s. They

could have done a lot of the work with horses.”24

At that time there was a cable car across the river.25

The first landing field was a meadow

approximately one mile from South Fork (Big Salmon River), about three

miles west of the Livingstone townsite. Lloyd Ryder recounts, “That

runway was done by hand, pulled all the stumps and stuff with pry-poles.

It was in good condition. There were no Cats out there in the ‘30s. They

could have done a lot of the work with horses.”24

At that time there was a cable car across the river.25

The first known flight to this field was in 1938, recorded in the photo above.26 The plane was a Ford Trimotor owned by BYN (White Pass), piloted by Ev Wasson27 with co-pilot Norman “Buck” Stone. Passengers were White Pass deckhands Solomon Charlie and Taylor McGundy, and Livingstone miners including Dan Snure28 (center).

A second airstrip was built by Louis Engle in the early 1950s with a D2 Cat, about two and a half miles from the Livingstone town site. It was upgraded and enlarged from 100

feet x 1200, to 250 feet x 1800 feet, by Al Serafinchon and Gerry McCully of

Constellation Mines in June/July, 1971.29

Airport Chalet at Livingstone Airstrip 1971, Ken Jones Photo

A small dirt-floored shack at the side of the airstrip was affectionately known as the Airport Chalet and sheltered people, sometimes for days at a time, waiting for their plane. The inside walls were covered with the graffiti of many years. Al Serafinchon made the signs pointing to the creeks in 1971. For some years a red mailbox was nailed to the logs next to the door. Jim Greer made the door and covered it with plastic. A very small woodstove gave an indifferent heat.

The airstrip was often the gathering place for people from all over the creeks, an opportunity to gossip, swap mining stories, and make deals. The sound of an incoming plane could create a stampede of people arriving on foot, by truck, “swamp buggy” and motorbike, hoping for mail, tobacco, and alcohol, or to snag a trip out. Often a plane would alert the party it was intended for by flying overhead, waggling its wings. This did not prevent the occasional “theft” of a plane when an enterprising individual arrived at the airstrip ahead of the person who’d ordered it, and convinced the pilot to take him instead.

Sometimes messages were air-dropped from a plane in a tobacco tin, weighted with a rock and flagged with bright orange engineering tape. In 1974 the Liberal party sent out a plane to bring voters into Whitehorse for the Federal election. A few Americans without Canadian voting rights got on board too. Nobody complained.

Pilot and aviation historian Bob Cameron says “regarding Livingston - local airplanes and pilots have been going in and out of there as far back as I can remember. Pretty well all of us who have flown commercially out of here [Whitehorse] (not counting airline pilots) have done trips to Livingston with Beavers, Otters, Cessnas, etc.” 30

Cameron made frequent flights to Livingstone between 1971 – 1975. His first flight was an emergency trip at midnight June 23, 1971 in TNTA’s (Trans North Turbo Air) Beaver to pick up pilot Harold Hoobanoff and passengers Ace Parker and Doug Craig, who had just crashed on take-off in a Cessna 172. The pilot seat had come loose, sending Harold sliding into the back of the cabin just as the aircraft became airborne, causing the plane to cartwheel. The pilot and passengers escaped with scratches.

Pilot Ed Phillips (L), Max Fuerstner, (R), and flipped Cessna 185. YA 2003/05 #14 McCully

Two or three years later Ed Phillips flipped a Cessna 185, C-FZRA, upside down on landing in heavy wet snow on wheels. Again there were no serious injuries. Two earlier crashes were a Great Northern Airways Beaver (CF-MAS) which crashed on take-off in spring of 1968, and a Mooney that went down in 1969.31

Great Northern Air’s CF-MAS ca. 1968 YA 2003/05 #13 McCully Coll.

Other aircraft flown to Livingstone were a 206 Cessna piloted by Ed Phillips, a Beaver belonging to Great Northern Air piloted by Lloyd Ryder, and a DC3 owned by Northward, which carried a large fuel bladder, piloted by Bill Dayton.32

Rene Leduc was a helicopter pilot. He also flew a Cessna 206 that belonged to Elvin’s Equipment that he later purchased.33 He owned a small Suzuki trail bike that he modified with a hinge plate so that it could be folded into the hold of the plane and used for running around the creek roads.

Helicopters have been a part of Livingstone’s aviation history, with their ability to fly directly to the claims on the creeks.

Pilots were sometimes reluctantly involved in tragedies as when, in the 1980s, Peter Kelly flew a helicopter out with the coroner to retrieve the body of a young man who died on one of the creeks. Sometimes the flights were rescue missions. In June 1953, Stan Clethero walked out to Whitehorse to get a plane for Louis Engle who was ill from food poisoning. A week later Stan’s own father was so ill with cancer that Stan again had to walk out to summon help. This time a helicopter came, but was unable to land close by, so Stan had to carry his father three miles on his back to the airstrip. William Clethero died in hospital two weeks later on June 26.s34

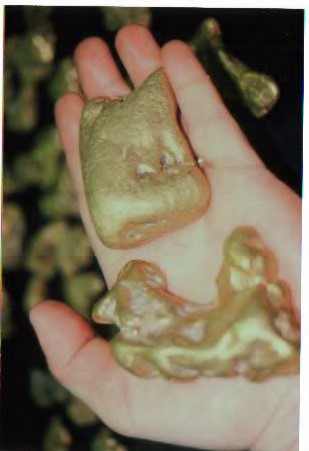

Waiting for the plane, 1974, YA 2003/05 #12, McCully Coll.

Back row (L -R) Matthew Wilkie in truck, Mary Greer, Jim Greer, Ed Hill, Augie Hill Trexler, George Asuchak Sr.,

Lee Wilkie (Leslie Hamson), Ronnie Asuchack, Bob Miller, Georgie Asuchak, Steve Ames. Front row (R-L) Todd Ames, Gerry McCully & son Jonathan, Burr Mosby, Dick Young Photo by Max Fuerstner Sr.

Pilots to Livingstone were also witnesses to amusing incidents. Bob Cameron was hired to fly Sheriff Al Adams out in the late fall ca. 1974 to seize a pickup truck for nonpayment. The flight was made in a Single Otter ski plane. The truck was found frozen into a glacier that had formed in a dip of the trail. It had been brought to Livingstone over the winter road by Armand Arsenault, who arranged to sell it to Gerry McCully, but no payments had been made. When Arsenault learned where the truck had been found, he commissioned a helicopter to fly to the location, stuffed the truck full of dynamite and blew it up. The following spring, McCully scavenged the parts that had been protected under the ice to repair another old Dodge pickup, creating a serviceable vehicle.35

Mining activity in the Livingstone district dropped to minimal as of 2003. According to